Every single human person brings his or her perspective to an event he or she covers.

It is true that when a person’s job is to provide a straightforward match recap (which is not what this or any Bloguin site is meant to do — not centrally, anyway), there’s less room for commentary, so in the match recap, which is slightly different from a “match analysis” piece and even more different from a “match reaction” piece, a person can remove his or her natural bias to simply “report the facts.”

In the realms of news analysis or editorial commentary, however, the perspective of the person inevitably shapes the tone, tenor and trajectory of what’s said. This is not “bias” in the sense of being unprofessional. This is “bias” in the sense that we all bring a bias to the way we perceive events of consequence.

To a certain extent, this is lamentable: If Israelis and Palestinians, Republicans and Democrats, Pakistanis and Indians could come together and find ways to emphasize their shared humanity, the world would be a better place. However, in a broader sense, thank goodness we all bring a different perspective to the table in many cases. If human beings all saw the same events in the same way, there would be no way to appreciate a different way of being, no way to realize that beauty and nobility and skill acquire many forms, not just the one “we” — our own tribe or in-group — might prefer.

For every “we,” there’s also a “they,” the tribe outside our own, the out-group. Tribalism is one of the most ugly forces known to humankind these days, but its ugliness does not cancel out the saving grace of knowing that the individual person can find many different paths to the same endpoint of fulfillment, of satisfaction, of peace, of a life well-lived, a life well-appreciated.

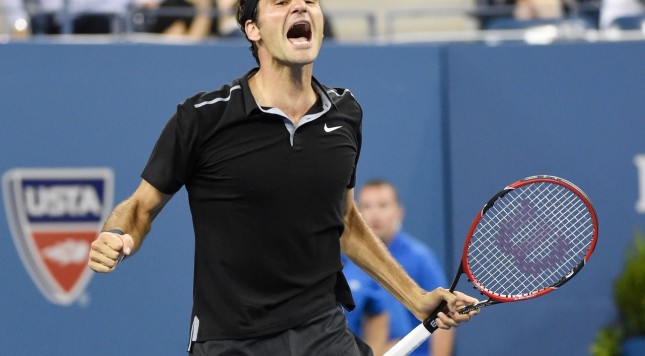

It’s this appreciation for differences which makes Roger Federer’s five-set win over Gael Monfils on Thursday night in the U.S. Open quarterfinals such a difficult event to fully describe… at least if the goal of describing the match is to satisfy every major constituency in men’s tennis:

A) Federer fans;

B) Nadal fans;

C) Djokovic fans;

D) Fans Of Other Players, aka “FOOP”

E) tennis diehards;

F) casual American sports fans who really like tennis

G) casual American sports fans who tune into the U.S. Open and Wimbledon each year, the way fallen-away Catholics still go to Christmas and Easter Mass, seeing if there’s anything they might find of value, but not being convinced they’ll find something transformative.

Steve Tignor of Tennis magazine filed his match report here, with quotes from each player’s press conference. Tignor is excellent at his job, so his report offers a good place to get the immediate sense of what happened, if you missed the match because you were either sleeping in Europe or watching Packers-Seahawks here in the United States.

*

I’m an American who really loves tennis, but I was more “a sports fan who loved tennis events” growing up, as opposed to “a tennis diehard who also loved other sports.” I’m not a tennis nut, but as I’ve followed the sport more and more closely over time, I’ve become more able to identify with the wishes of the diehard tennis fan. It should not come as a shock that at the U.S. Open, I become particularly sensitive to the tensions between “Tennis America” and “Casual Sports Fan America,” tensions which are very difficult to resolve yet carry implications for the way this sport will be treated in the future by broadcast media and the American viewers who are forced to view tennis through that prism.

So many parts of this U.S. Open and the way it has been covered on American television have stirred up my emotions as a lover of the sport who wants to see it gain more of a foothold in America. This article by Richard Sandomir of the New York Times puts so many of these tensions into context, and the details of Sandomir’s piece are precisely why — when this tournament ends next Monday — you’ll be sure to get a commentary from me on both the way tennis is viewed in the United States and the way in which this tournament was televised. With this in mind, let’s try to make sense of Federer-Monfils in a way that honors the facts of the event yet enables various tennis constituencies — the ones mentioned above — to think that their place at the table is being respected.

*

Yes, if you don’t care to read a lot of words about Federer-Monfils; if you want to know what happened in a very simple way, you could just look at these two photos below:

If you want to read some words about Federer’s 4-6, 3-6, 6-4, 7-5, 6-2 win over Monfils, continue on…

*

The most surprising aspect of Federer’s performance on Thursday night — it was not a good one — is that the Swiss had become a very good wind player. Recall this other nighttime U.S. Open quarterfinal against a much more accomplished player than Monfils? Federer wasn’t always a great wind player; when at his peak, the wind slowed him down and took him out of his full-flight, free-flowing game. Impatience with conditions could throw off his timing, but an accumulation of experiences led Fed to take on the challenges of such a situation. In the fourth round of this tournament, against Roberto Bautista-Agut, Federer dealt with a considerable wind inside the lower bowl of Arthur Ashe Stadium, so the prospect of dealing with more wind against Monfils should not have been a concern for the No. 2 seed.

Yet, on Thursday, it was. Monfils — this newer, steadier, less volatile tennis specimen — played the role of the solid, low-mistake opponent in this role-reversal tournament, and that’s why Federer found himself in a two-set ditch. He was losing against the wind, and against the Gael that remained firmly in his face. Much like his only previous loss in a U.S. Open night session — the 2012 quarterfinal setback against Tomas Berdych (who lost to Marin Cilic in Thursday’s afternoon quarterfinal; we’ll have much more on both men in our tournament wrap-up next week…) — Federer simply couldn’t find a rhythm.

Again, though, this came as a surprise. Federer played a fourth-round match this year. In the 2012 U.S. Open, a Mardy Fish walkover in round four left Federer cold and rusty heading into that Berdych match, so it was understandable that the Swiss was not sharp in the face of an assault from one of his few non-Nadal, non-Djokovic nemeses. Having dealt with the wind two days earlier, Federer simply could not hit his forehand with any lasting consistency in this match. Sometimes crosscourt and especially down the line, Federer lacked crisp timing all night. Part of this was rooted simply in a mediocre night at the office, but a big part of the dynamic was the product of two things:

1) Gael Monfils kept his stat sheet noticeably low on errors through the first two sets;

2) Monfils was able to cover the court and hit with a highly effective combination of pace and angle when he retrieved shots.

Monfils redirected the ball so well in the first two sets, continuing to manifest the new version of a player who has been so exasperating over the past several years. Federer wanted to get Monfils out of his comfort zone, so he rushed the net a lot, but he often did so from less-than-advantageous positions, and Monfils was usually able to outfox him in exchanges at close range. Federer was unsettled, Monfils the picture of stability. This twin reality stood against the past eight years of tennis history, but on this night, it could not be denied.

*

Gael Monfils, in many more ways than one, truly stretched himself at this tournament, expanding his sense of what’s possible for him and his career. If he views this loss as a building block and not as a wasted moment, he can — at age 28 — make a run at a major title before he’s done. Stan Wawrinka won his first major earlier this year at the age of 28, after all.

Why are we here, then, looking back on a Federer win?

It’s one of the great contradictions and paradoxes of this Golden Era of men’s tennis: As someone else (someone who values her privacy/anonymity) told me on #TennisTwitter a few years ago, “Rafael Nadal loves to make things look difficult, even when they’re easy. Roger Federer loves to make things look easy, even when they’re hard.” A truer, more distilled essence of these two remarkable tennis legends has never been expressed. Nadal relishes suffering on court the same way Federer relishes elegant, fluid play.

Yet, from that paradox emerges a pair of powerful truths about Nadal and Federer: Nadal — who needed time to become a complete, all-surface player in his career — ripened into a world-class shotmaker and performance artist, much more than just a wall of defensive mastery. Similarly, Federer — for all his desires to make things look easy and artistic — maintained his place at the top of the men’s game by developing world-class survival skills. Nadal and Federer own their primary identities, yes, but they have supplemented them with considerable resources in the realms that came less naturally to them as tennis players.

Very simply, then, Federer’s survival skills won this match for him.

Broken on serve and still fighting himself early in sets three and four, Federer didn’t allow negative events to overpower him and hijack subsequent games. In the pivotal fourth set — which just about everyone knew was either going to close down the match for Monfils or lead to a fifth set in which the No. 20 seed from France would have nothing left on a mental level (recall his fifth-set disappearing act against Andy Murray in the French Open quarterfinals this year) — Federer missed highly makeable groundstrokes from winning positions on 15-30 points in consecutive games, first at 3-3, then at 4-4. Monfils was no longer landing his first serve consistently, but Federer could not take advantage. This is why Federer had to serve at 4-5 to stay in the match, and it’s why at double match point for Monfils — 4-5, 15-40 — Federer had the appearance of a man who was going to fully succumb to pressure, as had been the case through most of the first four sets.

On the two match points he stared down, though, Federer — separating himself from most of his peers — played airtight points. A Monfils passing shot at 15-40 seemed to hang in the air for three years, not three seconds, but it was not a high-percentage look (Monfils caught it late off a solid but not spectacular approach from Federer), and it landed long by a full foot. Federer authoritatively saved the second match point, and he convincingly went on to hold for 5-5.

Monfils did have double match point, but much as Novak Djokovic wrested away two match points from Federer in the 2010 U.S. Open semifinals, Federer won those two match points in ways that left Monfils with no regrets (not on those two points, to be clear). The underdog simply had to acknowledge that Federer had played well in a moment of crisis. Monfils’s tripartite task was to hold for 6-5, try to receive out the match for 7-5, and mentally gird himself for a likely impending tiebreaker, a crapshoot in which an underdog should welcome the chance to win a handful of points in order to take the match.

*

For nearly four full sets, Monfils held himself together. If one is tempted to say that the whole of this match was “Same Old Gael,” that characterization seems a bit too extreme and unfair. If this was Old Monfils, the fourth set would have been a Federer runaway, followed by the similar one-way traffic which ensued in the fifth. Monfils took a stand for much of the fourth set. Though Federer helped him out with timely errors, mostly on that AWOL forehand wing, Monfils was able to hit aces or service winners on a number of break points, deuce points, and 30-30 points in that set, keeping his nose in front long enough to put the knife at Federer’s throat.

It wasn’t until 5-5, deuce, that Monfils — with a nod to his sometimes-crazy countryman, Jo-Wilfried Tsonga — finally cracked. Monfils had double-faulted earlier in the match to give Federer a break chance, but Monfils did something far worse this time: He served up the dreaded “double double” to directly gift Federer a break, not giving the struggling Swiss a chance to shank a forehand on break point.

Nearly three hours of excellent work put Monfils on the brink of not only a major semifinal, but a chance to play Marin Cilic and not a dream-crusher named Nadal or Djokovic. In those two double faults, though, Monfils recalled his old self and put the new one — sadly — on the shelf. He became a better player at this tournament. He showed dimensions of self that few tennis fans thought they’d see. Yet, much as a baseball team has to get the last out or score the last run, a tennis player has to win the last point. Gael Monfils couldn’t get there, and as someone who saved five match points to defeat Federer in the Paris (Bercy) Masters 1000 tournament in 2010, the Frenchman tasted the other side of tennis cruelty.

*

We arrive at the point in this piece where we must make sense of this event for Federer and what it means for his career.

Nadal fans will be quick to remind others that Rafa isn’t in this tournament, and that Federer is lucky he’s the No. 2 seed, safely out of both Rafa’s and Djokovic’s path until the final. Djokovic fans will focus on that last part, too.

It’s also true that Federer was resoundingly average in this match, continuing an American hardcourt summer in which his A-game — which emerged in the first four rounds of Wimbledon — has simply not surfaced. If you’re expecting hyperbolic words about the quality of Federer’s tennis, you’re not going to find such words here.

However — and this is where Federer’s most persistent critics and the fans of his foremost rivals need to check their criticisms at the door — an athlete’s achievements can still sparkle and resonate, even as the pure quality of play fails to rise to great heights. Federer’s tennis against Monfils was average, but the achievement somehow forged against the run of play through most of the first four sets is what merits praise — not just from the worshipping Fed fans or the casual American sports fans who respond to tennis icons and few others, but from any commentator whose job it is to put a moment into perspective.

You’re not a Fed Kool Aid-sipping devotee if you dare to point out that Federer has made three semifinals or better in the majors at age 33, something Jimmy Connors did in 1985… and which longevity-bearing greats such as Andre Agassi and Ken Rosewall failed to do at a similar age. Shouldn’t (wouldn’t) any commentator feel that such a statistic bears mentioning within the larger run of tennis history? That’s not a particularly normal or common feat — seems pretty newsworthy to me.

It’s not a manifestation of “Fed worship among bloggers” if one points out that Federer has increased his record-setting major semifinal total to 36, or if he’s reached a ninth U.S. Open semifinal, or if he’s cracked 8,000 ATP rankings points, or if he’s put himself in position to move within 160 points of Nadal for No. 2 in the world if he can beat Cilic on Saturday… all at the age of 33, when most tennis players — in this physically demanding modern game — just don’t deliver substantial results.

One would like to think that mentioning these achievements is nothing other than an act of mentioning newsworthy items to come from a newsworthy event. When Nadal and Djokovic win late-stage matches at majors, they reach new milestones and elevate their places in history as well. Much as no player should be exempt from blame if he loses in an appalling way (cough, Tomas Berdych against Cilic, cough), no player should be exempt from praise if he wins.

*

Yes, Federer didn’t play well against Gael Monfils. Yet, he won.

It matters that you should be told Federer didn’t play good tennis, especially if you are a Nadal or Djokovic fan, or even a casual sports fan who is inclined to think that this was a classic match. No, this was classic drama, but not classic tennis. Any sane person should be able to agree on this point.

It is, however, a timeless and accepted measure of greatness that the most accomplished athletes win on nights when they’re far from their best — it is how the legends separate themselves from the also-rans and the “almost players” in any sport.

Federer’s tennis on Thursday and at this U.S. Open? Blah — it hasn’t been that great.

Federer’s ability to win in spite of it all, to continue to achieve richly at an age when most tennis players have little to nothing left in their careers? That’s special… as are the achievements he continues to compile.

Mediocrity from a loser matters, because a consistent loser on the tennis tour demands the ability to rise above that mediocrity in order to win.

Mediocrity from Roger Federer matters when his opponent is able to drive the stake into his heart, but on nights like Thursday, when the Swiss finds a way to fend off the wind, a full-blown Gael, and the sands of time, mediocre tennis doesn’t matter.

It’s a very inconvenient truth for a lot of people, sure… but the truth is much more important and lasting than its inconvenience.