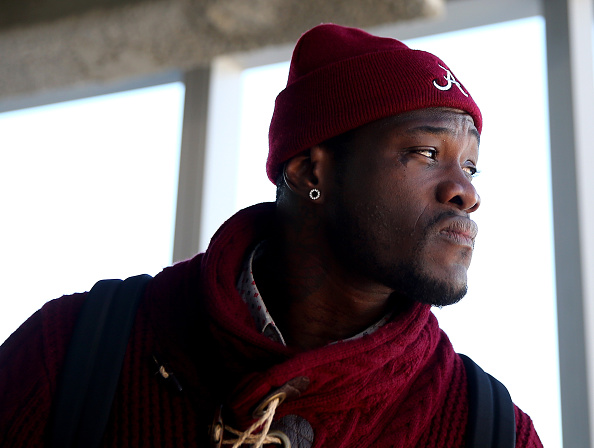

In Deontay Wilder’s mind, he was probably the best waiter at that IHOP restaurant in Tuscaloosa. He was developing his social skills, trying to turn people’s smiles into bigger tips, and he was flashy, taking the food and drink orders of customers without writing a word of it on a pad. Wilder could just remember the order.

He had started as a busboy, the one who collects the dirty plates off the abandoned table and wipes it ready for the next customer. But after a few days, Wilder’s manager moved him to a more high-profile role, where his personality could charm and his tips could grow.

A decade later, Wilder remembers those days with a warm spot in his heart. He never found himself drowning in the weeds (restaurant parlance for being overwhelmed with too many tables and too many orders), and his regular customers jockeyed to sit in his section.

He says he was — and is — a humble man, but yeah, it’s clear when talking to Wilder that the dude thinks he was the best waiter in the joint.

Now, Wilder is one of the heavyweight titlists, and at 35-0 with 34 knockouts, he’s one of the most intriguing boxers in that division. He’ll defend his belt Saturday night vs. Artur Szpilka (20-1, 15 KOs) at what should be a packed Barclays Center in New York, as he keeps moving toward the goal of unifying all four titles. But he hasn’t forgotten his times at IHOP.

Or working at Red Lobster. Or delivering beer.

It’s not because he loved working those jobs. It’s because he didn’t have a choice. It’s because he needed them to keep his family, including his ill baby daughter Naieya, afloat. He needed those low-paying jobs to survive.

“I could never see myself going back to a restaurant job, but I had to do what I had to do to support my family,” Wilder told The Comeback last week. “Of course I didn’t like the jobs I worked. I didn’t like not doing what I wanted to do. I didn’t feel like I was living when I was in the restaurant business. When you’re living paycheck to paycheck and you have only $30 for groceries, you’re just surviving. That’s not living. But my daughter couldn’t tell. We had a roof over our heads. We were eating.”

http://gty.im/490201242

That wasn’t supposed to be Wilder’s path. He was a 6-foot-7-inch football and basketball star at Central High School in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and he was enrolled at Shelton State with an eye toward eventually playing Division I football, hopefully with the Crimson Tide. But then he discovered he was going to be a dad, and soon after, while his daughter was still in the womb, he learned that she had Spina bifida, a condition causing birth defects in the spinal cord.

This meant that Naieya might never walk, might never control her bladder, might never have a normal childhood. At that moment, Wilder knew his old life was over. His new life, as a waiter and a provider, had begun.

“I knew what I had to do,” Wilder said. “It was an automatic thing where I had to get a job. There were always opportunities to go back to college. I could be 75 years old and go back to college. But during that time, I was looking for more money and a way to better our lives. She was my determination. She made my life better. When she was 1 year old, I told her that daddy was going to be a world champion and that I was going to be able to support her beyond belief.”

http://gty.im/490200192

While growing up, Wilder could always handle himself when an argument turned physical, and after dropping out of college, a buddy told him he should check out the local Skyy Boxing gym. When Wilder walked in that first day, he says he heard angels singing. No, literally. He heard the “Hallelujahs” and everything.

“I stood at the door,” he said, “and that feeling was like, ‘Wow. This is it.'”

Jay Deas, who owns the gym and who has trained Wilder his entire career, could sense something different about him. Sure, he was big, and he was athletic. But Wilder had something more. Wilder was tough. He worked hard even when he thought he wasn’t being observed. He was a natural.

That was proven when, after only 20 fights as an amateur, he won the Olympic Boxing Trials and went on to take home the Olympic bronze medal at the 2008 Beijing Games.

http://gty.im/82525785

Soon after, he turned pro, facing a long string of nobodies and glass-jawed stiffs. He’s been managed expertly and matched extraordinarily well (look at his knockout percentage, after all), and the biggest knock on Wilder at the moment is that he hasn’t beaten an elite fighter — the closest he came was lifting the heavyweight belt off the sturdy, but not spectacular Bermane Stiverne a year ago. Perhaps Wilder hasn’t received the credit he deserves, but that’s because nobody seems to know if he’s really earned it in the ring.

“Everybody thinks he was this phenom who came in and had it from day one,” Deas told AL.com last June. “That’s not the case. He had the will to win. He had a hard punch. He had tons of athleticism. The rest, he worked really, really hard for. That’s the part people don’t understand. He didn’t just take to it and start knocking people out. He worked to get there …”

http://gty.im/490201020

He hasn’t stopped working since — thanks to his motivation, the one who inspired him as he pulled those long 12-hour shifts at IHOP and the one who forced him to change his life for the better.

“Naieya is wonderful. She’ll be 11 in March, and she’s one of the brightest little girls ever,” Wilder said. “You could never tell she had any problems. She wasn’t supposed to be walking. But, man, she came out running.”