The NFL has fought hard to change the conversation around concussion research over the past few years, admitting to previous mistakes spotlighted in projects like League of Denial and Concussion. The league has promised a new approach, recognizing and funding scientific research in the field.

However, according to the latest bombshell at ESPN’s Outside the Lines from League of Denial authors Mark Fainaru-Wada and Steve Fainaru, the NFL hasn’t necessarily changed all that much, still interfering in and attempting to manipulate the research out there on concussions.

Yes, the NFL has new doctors in charge who had previously received praise for their concussion work, and yes, the league has donated large amounts of money to research. But many are questioning why much of that research money is going to doctors with NFL ties, with at least six grants in the last two years going to “scientists or institutions directly connected to the league,” and some others specifically not going to those who have been more critical.

Beyond that, even some of those who were once critics seem to be singing a different tune now that they’re on NFL committees, as described in this passage from a speech by Dr. Kevin Guskiewicz, who chairs the NFL’s Subcommittee on Safety Equipment and Playing Rules:

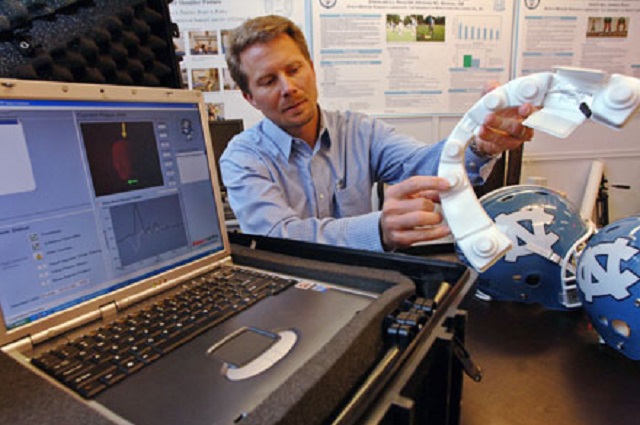

Last summer, 100 Ivy League and Big Ten scientists met in Chicago for a concussion summit. The keynote speaker was Guskiewicz, the concussion expert who led the proposal for the NFL-funded NIH grant. A former Pittsburgh Steelers assistant athletic trainer, Guskiewicz was named dean of the University of North Carolina’s College of Arts and Sciences last year, an achievement that followed two decades of research that helped turn sport-related concussions into a major public health issue.

Once a harsh NFL critic who compared the league’s “industry-funded research” under Pellman to an airport security breach, Guskiewicz is now part of the NFL’s Head, Neck and Spine Committee, which helps shape league policy. Some researchers believe that since affiliating with the league, Guskiewicz has softened his previous positions, including the conclusions of his own pioneering research. Guskiewicz said he has remained consistent: that previous concussions can lead to long-term consequences, including depression and mild cognitive impairment, but that much is still unknown about the connection between football and brain disease.

During his speech in Chicago, Guskiewicz downplayed the importance of “sub-concussive” hits, which some researchers cite as the likely source of brain disease associated with football. The theory is especially thorny for the NFL, because it would mean the damage is produced by the unavoidable helmet-to-helmet contact that occurs on every play and in practice drills.

Guskiewicz, in an interview this week, said the title of his speech was, “The State of Sports Concussion: Legitimate Concerns vs. Paranoia,” and that its intent was to be provocative for the audience of clinicians and researchers. He said he pointed out that previous research, including his own, indicates that repeated diagnosed concussions may lead to long-term problems, but that “the pendulum has swung so far on this notion of repetitive sub-concussive impact just because it, quote-unquote, ‘should make sense.’ And what I keep emphasizing is, ‘Well, let’s figure it out.’ Where’s the evidence to support this notion or theory?”

Dr. Hans Breiter, a Northwestern University psychiatrist and behavioral scientist, was in the audience. Breiter has worked closely over the past two years with Purdue’s Talavage and Nauman, who have researched the effects of sub-concussive blows on players.

“The whole group of us at our table were going, ‘What? You gotta be kidding me,'” Breiter said. “It was really bizarre. We all started to look at each other and say, ‘This is what happened with Big Tobacco.’ It felt like we were going back to the stage where the people who were funded by Big Tobacco were saying smoking is not harmful.”

This wasn’t just one speech, either, as Guskiewicz is a key player in the whole story and the most directly tied to NFL interference with funding. The league gave a $30 million pledge to the National Institutes of Health in October 2012, which it described as “an unrestricted gift” in a media release, but one that came with written agreements in which the NFL preapproved multiple research areas and can offer “research concepts” through a “stakeholder board. The pledge was also described as a “conditional contribution” in the NIH foundation’s financial statements.

How that funding would be used was particularly put to the test in an application for a $16 million grant for a research project on football and brain disease. One proposal was led by Guskiewicz and also involved Dr. Richard Ellenbogen (co-chairman of the league’s Head, Neck and Spine Committee), along with three others tied to the NFL: Head, Neck and Spine committee member Dr. Michael McCrea from the University of Wisconsin and consultants Dr. Bruce Miller and Dr. Geoff Manley from the University of California – San Francisco.

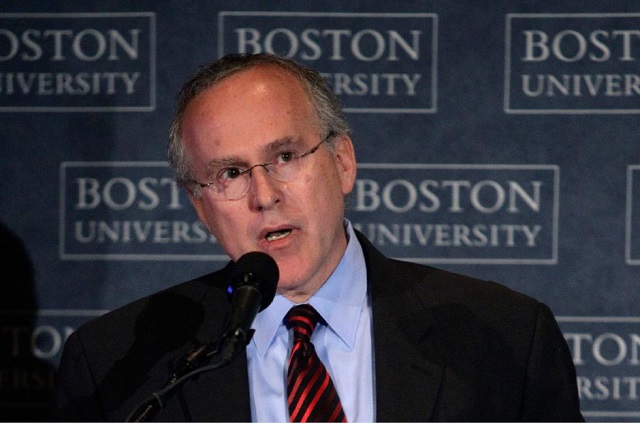

As described in a January OTL piece, the NIH picked a competing proposal led by Boston University’s Dr. Robert Stern, who had previously been critical of the league, and the NFL objected. Fascinatingly enough, OTL reports that one of the objections came from Ellenbogen, who was involved in the competing study.

This marks a change for Ellenbogen, as upon joining the NFL committee, he said “You can’t have the NFL doing studies. […] You gotta get people who don’t owe us anything.” This time around, he told OTL “We spend thousands of hours pushing the science forward for free because we want to answer essential scientific questions pertinent to our clinical practices. We are often in the best position to do it.”

However, the NIH didn’t think so, opting instead to go with Stern’s study after an exhaustive peer-review process. That led to the foundation being criticized on a June conference call by Ellenbogen, Dr. Mitch Berger (chairman of the NFL subcommittee on long-term effects of brain and spine injury, and a UCSF colleague of Miller and Manley) and Jeff Miller, the NFL’s senior vice-president for health and safety. Ellenbogen’s involvement, in particular, drew criticism from unaffiliated researcher Dr. Steven DeKosky:

“The idea that you would have anybody make that call who stands to gain, that would be just insane. You would never do that,” said Dr. Steven DeKosky, the deputy director of the McKnight Brain Institute at University of Florida, who once came under fire from the NFL after he and a former colleague, Dr. Bennet Omalu, reported the first case of brain disease in an NFL player. “That’s just inappropriate, if they were competing for the same grant and on the call to protest something about the guy who got the grant,” DeKosky said. “They should be nowhere near that.”

What’s also fascinating here is the continued involvement of Dr. Elliot Pellman, the rheumatologist and NFL adviser who led the league’s initial concussion committee from its 1994 formation to his 2007 resignation, and was crucial in the league’s denials. As the OTL piece writes, “Pellman was lead author on nine of the 16 NFL papers that described concussions as minor injuries. He and his co-authors once wrote: ‘Professional football players do not sustain frequent repetitive blows to the brain on a regular basis.'”

Pellman is now described as the NFL’s medical director and its primary contact on the grant to the NIH, and he sent an e-mail to the NIH complaining about Stern’s selection before that June conference call. Patrick Hruby wrote a great 2013 piece for Sports on Earth on how insane it is that Pellman’s still involved with the NFL and its research, featuring the quote that “Pellman’s continuing involvement with the league [is] the equivalent of having ‘the fox guard the henhouse.'” For the NFL to claim it’s being progressive on concussion research and yet have a widely-discredited figure like Pellman as the chief point of contact over its grant to the NIH is incredible.

In the end, the NIH came up with its own funding for the Stern-led study, so that research is still going to be done and still going to be published. (Hilariously, Ellenbogen told OTL “I do not know Dr. Stern and therefore do not have an opinion on him,” which seems highly implausible given the small world of concussion research and Stern’s high profile within it.) The question is if that will disappear in the noise from some NFL-affiliated studies which, as the OTL piece relates, have been used to remove helmet sensors (because they didn’t meet an impossible accuracy standard) and to downplay the importance of subconcussive hits.

Of course, some of the NFL funding is going to important research, and to respected concussion researchers like Boston University’s Dr. Ann McKee, but even she’s a little leery of whether that funding will be pulled, saying “I think you always feel like you’re on tenuous ground with them, always concerned that their commitment may not be long term, that it may be conditional.”

Given OTL’s account of how the NFL appears to be trying to influence research, that skepticism seems highly justified. Meanwhile, the numbers of concussions are rising, as are the numbers of former players diagnosed with CTE. Years since the events described in Concussion and League of Denial, the NFL claims everything about its approach to concussions has changed, but from the outside, it appears little has.