Rumble young man. Rumble.

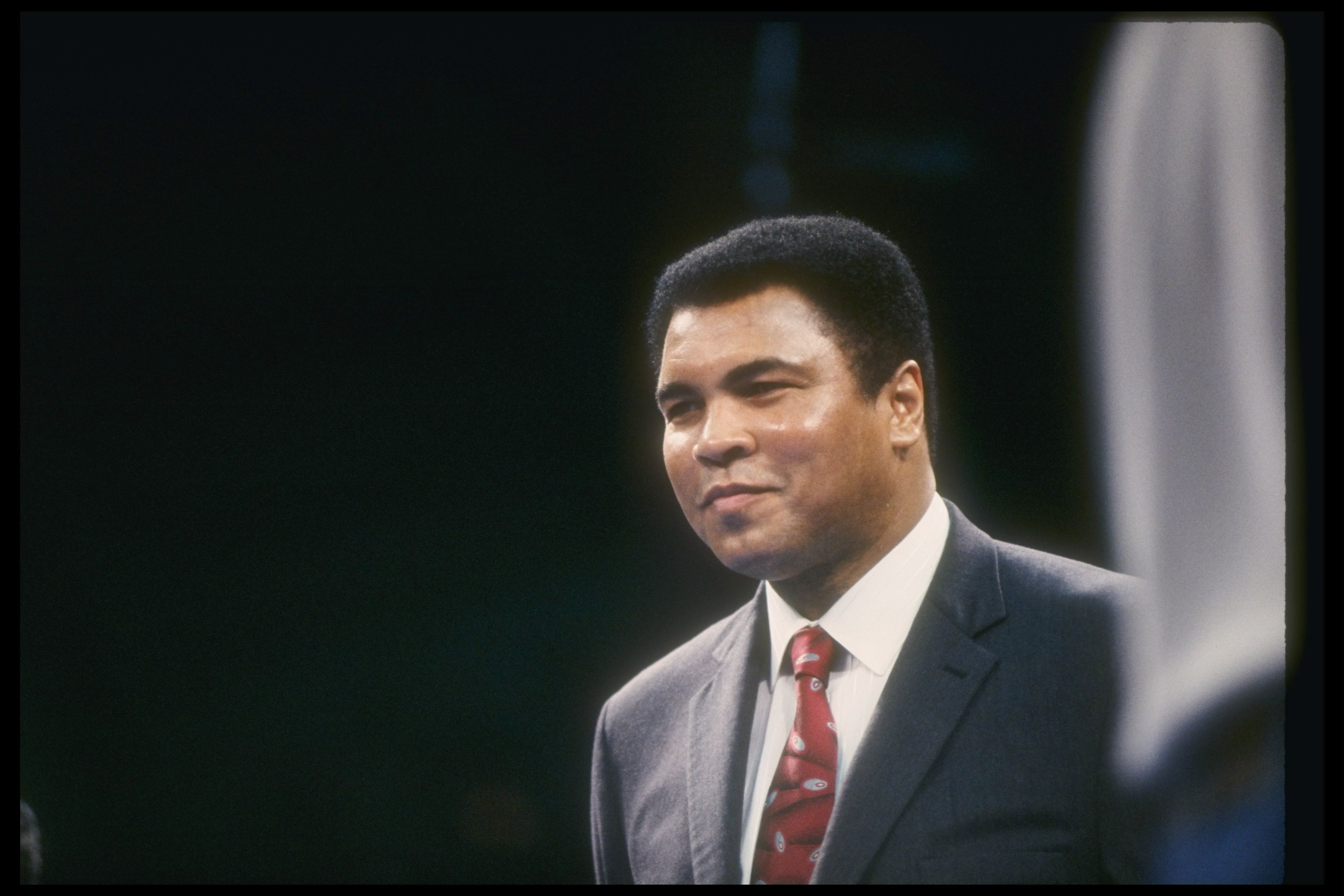

There is no one quite like Muhammad Ali. It feels impossible to put into words what a man so important to the world of sports—to our world in general—means on a day like this.

And yet we try. On a day like this we try to put into words the impact of a man who transcended sports, politics and popular culture. Ali was different than other great athletes of his day or, frankly, any day. Ali managed to do something very few men or women in sports have ever done.

Ali transcended time. Muhammad Ali is as popular on his last day as he was on his first.

You know, “popular” really isn’t the word. Significant seems more apt.

http://gty.im/3162458

Going from a relatively unknown amateur fighter to an Olympic champion, a 22 year-old boxer named Cassius Clay shocked the world in 1964 when he defeated Sonny Liston for the world heavyweight championship. Clay had begun a relationship with the Nation of Islam in the years before his first title fight and after defeating Liston, that relationship became permanent. Ali was born.

Molded from the body of a champion named Clay, Muhammad Ali became a completely different man for his time. For any time.

Throughout his career, and certainly since his fighting days ended, Ali became as renown for his proclivity to rattle off a memorable quote as he was for his prowess in the ring.

Whether or not Ali was actually a bad man he wanted everyone—especially his opponent—to believe it. He made sure everyone knew who was the greatest of all time, too. (Note: it was him.)

His use of animal metaphors was legendary. He called Liston a “big ugly bear” he was going to “donate to the zoo” at the same time the young star told the rest of the world he was going to “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.”

Who talks likes that? Who ever in the history of the world—sports or otherwise—talked like that?

Who would ever think to promote a fight—Ali’s was in rare form to promote his 1974 fight George Foreman, tabbed the Rumble in the Jungle—by saying all of this:

I’m bad. I’ve been chopping trees. I’ve done something new for this fight. I done wrestled with an alligator…I tussled with a whale. I done handcuffed lightning, thrown thunder in jail. That’s bad.

Only last week, I murdered a rock. Injured a stone. Hospitalized a brick. I’m so mean I make medicine sick. Bad.

Fast, fast…fast! Last night I cut the light off my bedroom, hit the switch and was in bed before the room was dark. Fast.

This is how we remember Ali today. The baddest. The fastest. The greatest, both in and out of the ring.

(Note: boxing historians would be the first to point out that while Ali used such effervescent phrasing to promote his fights, old punchers like Tony Galento actually did wrestle with sea creatures, once grappling with an octopus—and boxing a kangaroo—to promote a fight.)

Ali’s true impact started well before that. He was never really seen as the hero—the good guy—in many of his early fights. His brash attitude and bravado made him notorious, but it didn’t necessarily endear him to the boxing crowd. People came in droves just to root against him.

When Ali spoke out against violence and the Vietnam War, he moved beyond merely being a villain in a sports context. He became one of the most polarizing political and social figures in the country. In the world.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vuj8kfEG7fU

In 1967 when Ali refused to participate in the Vietnam War, it nearly cost him everything. His boxing license was stripped in every state. His passport was revoked. He had to fight to stay out of jail; remain a free man. Boxing seemed to have far less importance to him, and to his cause.

And yet, he was a boxer. The greatest boxer; unable to fight from the age of 25 to 29, the absolute prime of his career.

The decision cost him favor with many Americans too. Ali became something of a spokesman for the anti-war cause and, in doing so, a very pronounced anti-“whiteman” cause perpetuated at the time by Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam. Many people thought the group was “taking him for a ride,” indoctrinating Ali into their cause to use him as a recruitment tool.

In a very difficult time in this nation’s social and political history, Ali became a lightning rod for both sides of the cause. It’s hard to imagine an athlete in today’s society taking on what Ali did. The world today is so much different than it was then. The athletes are different too.

Ali’s fight was confusing for the media as well. Legally, he was still named Cassius Clay, noted in all court filings and even the Associated Press stories about his fight to be reinstated to boxing.

As a boxer, reporters called him Ali. As a political activist fighting for his freedom, they called him Clay.

He lost what should have been his greatest years as a boxer, but that battle didn’t break Ali. A lesser man would have been broken, lost, gone from the sport he loved forever. Ali was not a lesser man. That time in his life made him stronger. It galvanized him.

To this day, it defined him.

Ali did not throw a competitive punch from March 22, 1967 through October 26, 1970, but in that time he never stopped fighting. The longer he was kept away from the sport, the greater the shadow he cast upon the other top fighters of his time.

Ali fought twice upon his reinstatement before facing Joe Frazier in what was billed as the Fight of the Century.

Ali lost, for the first time in his career.

That first fight with Frazier had become about so much more than two men in a boxing ring. Ali used Frazier as a bastion of the establishment, repeatedly calling Frazier an “Uncle Tom” and suggesting that he was the fighter only the white elite could root for. It was not Ali’s finest moment, and the animosity that came from the lead up to that bout stayed with Frazier forever.

As a boxer, Ali rebounded after the loss to Frazier, winning his next ten bouts before losing his title to Ken Norton in 1973. Six months later, Ali defeated Norton to win back his belt, setting up an early 1974 rematch with Frazier. Ali won that fight then beat Foreman in the Rumble in the Jungle later that year to unify the heavyweight belts.

He was truly back on top of the sport and the spotlight had never been bigger.

Over the next three years, Ali won ten fights, including the Thrilla in Manila over Frazier in their last of three epic bouts. By that time, Ali was a much different fighter and a very different man.

He was still outspoken about his religious and political beliefs, but as time passed and the opinions around the Vietnam War changed in America, people’s views of Ali changed as well. He became far less of an activist, becoming something of a statesman as he matured.

That brash 24 year-old fighter would never have glad-handed with Presidents. An older and wiser Ali learned a better way to play the game.

http://gty.im/85942389

I never got the chance to see Ali fight—I was born just four days before the 1978 loss to Leon Spinks, one of three losses in the final four fights that ended his time in the ring—yet it feels like I was there for every big moment of his career.

I remember vivid details of his fights with Liston, Frazier and Foreman. The quotes in this piece, and countless others, are just part of the space around us. Kids today probably float like butterflies and sting like bees without even knowing from where, or from whom, that idea came.

To this day, his greatness transcends time.

Ali never needed a hype man. He was the greatest hype man in history. He didn’t need an entourage to lead him into the ring. The world was his entourage.

Even after he retired from fighting and succumbed to the effects of Parkinson’s that riddled his body and took away his ability to speak like he did as a fighter and an activist, Ali had a spark and charisma that could make the world—his world—stand still.

In and out of the ring, Ali was the greatest. There are no other words.

http://gty.im/1847814