There have been plenty of disturbing studies on the long-term effects of concussions and football, such as July’s revelation that 110 of the 111 brains of former NFL players studied by Ann McKee and the Boston University/Concussion Legacy Foundation group had chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). However, many severe neurological diseases like CTE can only really be diagnosed after death (although there are some attempts to change that), and some leagues and teams have downplayed the severe symptoms former players complain of by attributing them to natural aging and downplayed the numbers of CTE diagnoses by playing up the self-selection factor.

It’s been difficult to really examine the effects of football on living former players in a rigorous scientific way, but a new study by The Hamilton Spectator and McMaster University (both located in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada) does that, and one researcher involved said the results they found were “shocking.” It’s interesting to see a local paper partner with a university like this on such a long-term project, but it certainly appears to have produced remarkable results.

The study examined nearly two dozen former CFL players, as well as a control group of similar size, over the past two years. It ran a wide variety of neurological tests on both groups, and the paper’s write-up (by renowned investigative reporter Steve Buist) says “We believe this is the first study anywhere to report findings from living former football players using such a wide array of tests.” But it’s the results that are really troubling. Here are some descriptions of them:

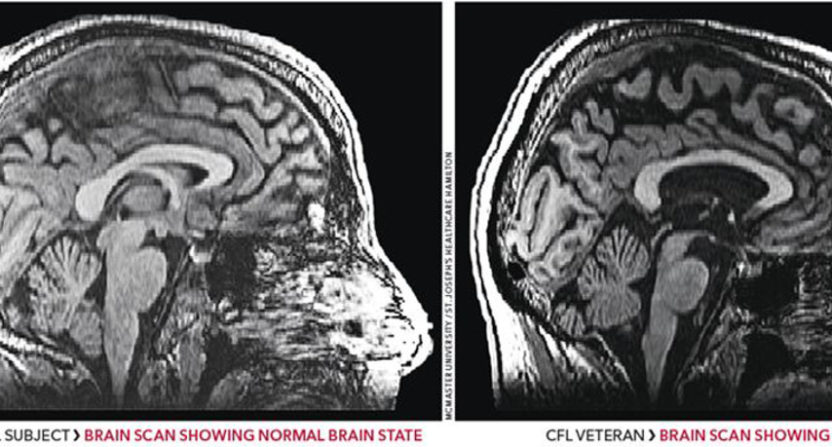

In some cases, the results from former players were no different than the results that would be seen in coma patients. Brain images from some retired players in their 40s looked like the images of men in their 80s.

On average, the retired players’ brains showed a 20 per cent reduction in the mass of the cerebral cortex, where billions of nerve cell bodies reside.

…Compared to healthy control subjects of similar ages, the retired players showed:

• Widespread thinning of the cerebral cortex, which helps organize thought and high-level processing. The findings suggest the players, on average, have lost significant numbers of nerve cells in the brain;

• Significant areas of differences in the bundles of nerve fibres that connect various parts of the brain, which suggest potential problems with information processing in the brain;

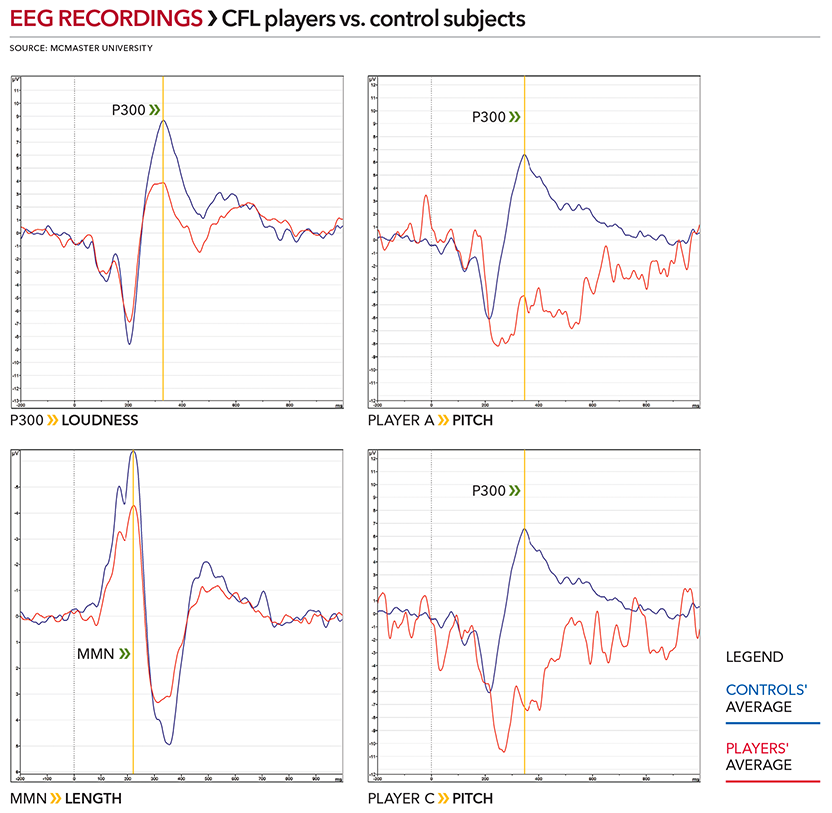

• Sharply lower levels of electrical activity in the brain from EEG recordings, which supports the finding that nerve cells have been lost in the cortex;

• A 10-fold increase of memory-related symptoms and a four-times increase in depression symptoms. Sixteen of 22 retired players reported some level of memory problems, compared to two of 20 control subjects.

Here’s a look at the electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings, which show just how unresponsive these players’ brains to stimuli compared to control subjects of similar ages:

Yeah, that’s not good, with specialists saying it means “they cannot pay sustained attention,” and the lack of P300 results in particular being astounding, and comparable to some coma patients. That’s only part of the testing done, though. There were also MRIs showing drastically reduced cortical thickness with less nerve cells (with 65 per cent of the cerebral cortex area and 20 per cent of its mass showing significant thinning and loss in the players compared to the control group; some of that can be seen in the photo at top), suggesting that players in their 40s “have the brain of an 80-year-old, maybe 90-year-old.”

The article goes into much more detail on those and other findings and what they mean, but the takeaway is potentially disastrous for football. It’s yet more proof that the CFL is facing a major concussion crisis of its own, something that should be apparent from the hundreds of former players suing the league, but something that’s also often been downplayed by league executives.

This also has major implications for the NFL and NCAA. The data here suggests yet more disturbing things about the impacts of football on players’ brains (and subconcussive hits as well as concussive ones; it mentions that linemen, who tend to have a lot of the former, fared particularly badly here). It also helps refute some of the arguments made against the significance of concussions, particularly those that say players’ neurological issues are about aging or other factors. This study’s particularly useful for showing just how much worse these players’ brains are compared to other people their age.

Is one study the answer to everything? Of course not. There are some limitations here, especially with the group size (which is decent for something done over this long of a period, but not huge overall), and the results may not be universally applicable. But this is an important addition to the growing field of concussion studies, and one that says some very interesting things about how severe the brain damage from football can be.

It also says a lot about what that means for players’ lives afterwards. McMaster professor Dr. Luciano Minuzzi (one of the key researchers on this study) had some particularly strong comments about the cortical thinning, how dramatic it was, and what implications came to mind for him:

Minuzzi, the psychiatrist and brain imaging expert, said he expected to see small spots of cortical thinning, perhaps localized to the areas where concussions occurred.

Instead, “they show global reduction,” Minuzzi said. “The whole brain has been affected.”

…“Something really wrong is happening here,” he said. “It’s impossible to fake this. This is an objective measure of the thickness of your brain.”

…As Minuzzi studied the brain scans of the players, one image popped into his head — “the gladiators of the past,” he said.

“People were cheering for someone to die,” he said. “I was wondering if that’s what’s happening now when we turn the TV on. Are we seeing people who are being exposed to something that is quite negative that will change their lives forever?”

That’s a good question, and the consequences of football certainly appear to have negatively changed many former players’ lives for the worse, both in the U.S. and in Canada. And that’s led some to walk away from even covering the game, including ESPN NCAA analyst Ed Cunningham this week. We don’t yet know the full rates or effects of football-caused brain damage, and we don’t know if or how much any of the recent safety measures from leagues, medical professionals and equipment manufacturers will help, but studies like this add to the pile suggesting that football can cause major brain issues for many of those who play it at a high level.

This study in particular is important for revealing how significant much of that damage can be even relatively soon after players’ careers end. The Spectator‘s full report here is worth reading, and they’ll have further follow-ups in the days to come (it’s also impressive that a local newspaper took on such a big and important project like this), but this one is already making a mark. And like Minuzzi, it may have many wondering what’s really happening when we watch football.

And ESPN’s OTL team of brothers is reporting that the NFL’s new “studies” are basically as crooked as the research funded by the tobacco industry.