Following a 37-7 road loss to unranked Mississippi State Saturday, it’s not surprising that the LSU Tigers are looking for some bright spots in their game notes heading into this week’s clash with Syracuse. And they found some stats that are certainly worth mentioning. However, they’re not necessarily a good indication that things are going to turn around:

Some positive numbers from #LSU game notes. pic.twitter.com/qrNp3krIYd

— Ross Dellenger (@RossDellenger) September 18, 2017

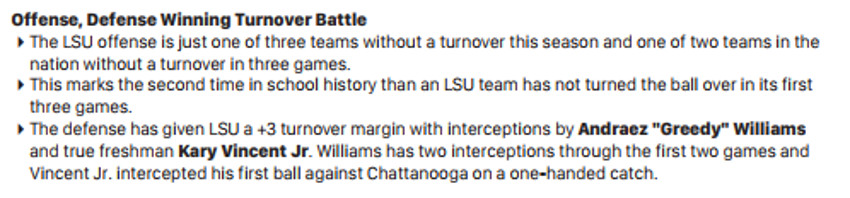

The full game notes (PDF) go into even more detail on the turnovers on page three:

This sort of thing is absolutely worth mentioning in game notes, and it’s a useful stat to know. However, it doesn’t necessarily bode well for the Tigers’ chances of turning things around after this loss. Yes, turnover margin is highly correlated to winning, and yes, there may be some ability to preach ball security on offense and ball-hawking on defense to improve it. But for one thing, the plus-three turnover margin comes thanks to an interception against 1-3 BYU (“one of the worst offenses in the country“) and two against Chattanooga (0-3, and a FCS team; Williams is seen breaking up a pass against them above), and for another, study after study has shown that there’s a huge random and non-repeatable component to turnovers.

Thus, it’s quite possible that there may be a downturn ahead for LSU, especially given that random component. For evidence of that, consider Bill Barnwell’s 2011 Grantland piece looking at turnovers through five games versus turnovers after a full season in the NFL:

Do teams that start the season sans takeaways swing back toward normalcy and start generating turnovers, or is a slow start indicative of a real problem with the defense? To answer that question, we can use the correlation coefficient, which we introduced in our Wednesday piece on the point spread. The correlation coefficient measures the relationship between two sets of variables and can tell us if one is a strong predictor of the other. What we’re trying to figure out is whether a team’s takeaway total during its first five games does a good job of predicting the same team’s takeaways during the final 11 games.

The answer is a very swift no. Less than 2 percent of the takeaway rates posted by teams during the final 11 games can be explained away by the variance of their takeaway rates during the first five. It’s a useless indicator. Put it this way — since 1990, the top 10 percent or so of teams in takeaways through the first five games each forced 14 or more turnovers. In the final 11 games of the year, they averaged a total of 21.6. Meanwhile, the bottom 10 percent or so of teams during the first five games of the year each forced no more than five turnovers. In their final 11 games, they picked up an average of 19.0 takeaways. After those initial five games to start the year, the difference between the teams that looked like takeaway factories and the ones that looked like they were incapable of forcing turnovers was just one turnover per every four games.

Yes, that’s a different level of football, but the general point holds; having your defense off to a hot start in forcing turnovers doesn’t mean you’re going to be at the top there by the end of the year. And this has been repeatedly found; consider this 2004 Football Outsiders piece from Jim Armstrong on the lack of predictability of turnovers, using data from the NFL from 1998-2003.

Here we see that offensive performance is much more predictable from year to year than defensive performance by any measure. And by far the least predictable of these drive rate stats is the defensive turnover per drive rate. This suggests that defenses have relatively little persistent ability to force turnovers. Perhaps if we were to dig a little deeper, we might find a few teams or players who do have such persistent ability to some extent, but in general it’s not at all an ability that is pervasive throughout the NFL. If a coach can teach such an ability, it’s probably so rare that most teams can’t do it to a significant degree year after year.

…A defense’s tendency to force turnovers is fairly important to the team’s success, but it seems to be even more unpredictable. In general, a team’s ability to force fumbles seems to be almost entirely luck. There is a little bit more persistence in a team’s ability to force interceptions, though it isn’t clear how much of this ability is just a residual effect of general defensive ability. Again, this only pertains to the team level. Whether there are some individual players with a special ability to force turnovers significantly above average rates would be an interesting subject for further study.

What about in college football? SB Nation’s Bill Connelly had some thoughts along the same lines at Football Study Hall in 2014:

Sometimes the ball lies, Rasheed, at least in football.

We can go pretty deep into the numbers to gauge who’s good and who’s bad, who’s efficient and who’s not. But the ball is still pointy, and it bounces the way it chooses to bounce sometimes. More than in any other sport, you have to be both lucky and good to win a lot of football games.

In my offseason preview series each year, I’ve tried to get at this idea by discussing turnovers luck. The concepts are pretty simple: Over time, you’re going to recover about 50 percent of all fumbles, but in a given year, you might recover 70 percent, or you might recover 30. The same goes with passes defensed; on average, you can expect to intercept about 22 percent of the passes you defense. (Passes defensed = interceptions + break-ups.) This is a bit mushier a concept, as we’ll discuss below, but over time a particularly butter-fingered year will be balanced by a sticky one.

It’s not all random, of course. As Connelly touches on later in that piece, there are some skill components involved, with some defenders and some defenses that emphasize ball-hawking versus knocking the ball down more likely to record interceptions. And on the offensive side of the ball, some running backs like LSU’s Derrius Guice have proven better at avoiding fumbles than their peers, and not all quarterbacks throw equal numbers of interceptions; Tigers’ senior Danny Etling has shown some skill in avoiding picks. It’s also notable that two of LSU’s picks came against FCS Chattanooga, where you’d expect the Tigers’ skill level to swing things their way.

But there’s a big luck component here as well. Julian Ryan of the Harvard Sports Analysis Collective ran a 2002-2013 NFL analysis in 2014 to try and figure out how random turnovers were, and found that 54.7 per cent of season-after-season turnover differential per team appeared related to luck:

So after a few hundred words of statistics, we arrive at a whopping conclusion that just over half of seasonal turnover differential is due to luck. That’s huge, especially when you consider that (from earlier) seasonal turnover differential explains over 40% of seasonal winning percentage.

LSU isn’t necessarily going to stop forcing defensive turnovers altogether and start committing offensive turnovers at NCAA-high rates, and it’s important to note the gambler’s fallacy here; a roulette ball landing on black does not make it more likely that the next one will land on red, as each is an independent event. Similarly, the Tigers should have close to the same odds of committing or capitalizing on both the next turnover and the turnover after that (they may not be quite independent, as score effects and momentum can alter things, but they’re not highly dependent), regardless of what happened on the last one.

In the bigger picture, though, there is a significant random component to turnovers. And you’d expect it to get more and more balanced in a larger sample size like a season, so LSU’s success there so far doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll keep winning the turnover battle. But the even bigger problem for the Tigers is that holding Mississippi State to a draw in the turnover battle (neither team had one) didn’t help them avoid this 37-7 beating. This team showed plenty of flaws Saturday that they’ll have to fix, and while they may well be able to improve (it’s one game, and doesn’t necessarily deserve an overreaction), they have a long way to go. And they may not be able to rely on continued success in the turnover game.

[LSU game notes vs. Syracuse]