Societies can be uneasy with boxing’s brutality. We watch two men coming as close to killing each other as the law allows. Some die, tragically, but not unexpectedly. In the aftermath of 2.2 million pay-per-view purchases for Floyd Mayweather and Canelo Alvarez this month, it bears thinking about why spilled blood on canvas is such a powerful draw. We watch it because it’s fun, of course, and thrilling to see the physicality. But boxing’s appeal goes deeper than just the love of sport. We use it to acknowledge the power of savagery in a distinctly civilized culture.

One of the cornerstones of our culture in the Western world today is tolerance. We don’t hate. Instead, we try to understand our enemy, whoever it is.

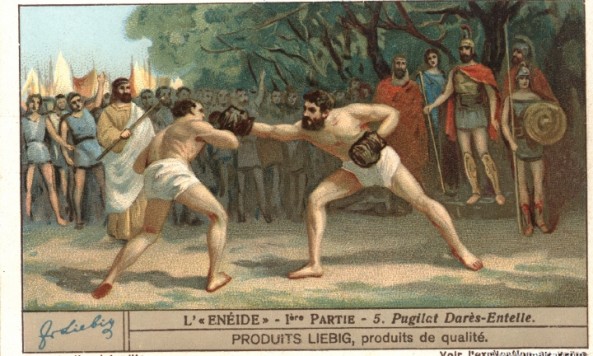

A deeply rooted part of us objects to this. On some level, we have an instinctual urge to see our enemies beaten, not understood. The more culture moves away from war, the more we need things to stand in its place to fill the gap. The Greeks and Romans moved away from funeral sacrifice by adopting sports, and we’ve kept the tradition.

Some writers even consider that boxing isn’t quite a sport. Joyce Carol Oates said as much in her profound, dramatic On Boxing:

“There’s nothing fundamentally playful about; nothing that seems to belong to daylight, to pleasure… one plays football, one doesn’t play boxing.”

We have other sports, certainly, but boxing is the only one where the clearly stated goal is to hurt the other man until he can’t get back up. Oates’ argument is that nothing so brutal could be so popular without a powerful resonance.

That resonance could be a few things, but the most basic a need to see blood.

In a society where war is distant and loathsome, it’s fair to say we’re removed from violence. Only the most unfortunate classes experience the daily reality of bloodshed. Boxing is a way for us to witness violent confrontation without the danger of death. Boxers are almost like sacrifices to pay the price of our civilization; they bleed for us because we don’t bleed on our own.

Other sports make people bleed on occasion, but boxing is so primal that it steps into a whole new representation of primitive conflict. Sports have rules and equipment. They’re built on the assumption of society.

Boxing has nothing but the weapons we’d use if two of us came across a pool of water that was only big enough for one. It takes us to a time where life itself was the prize where that prize was won toe-to-toe like Oates suggested when she wrote that boxing spectators “relive the murderous infancy of the race.”

Because it’s such a visceral way for us to relive that primitive violence, it’s especially prone to visceral and primitive patterns from the viewers. ESPN’s Nigel Collins recently wrote a piece on why it’s acceptable in boxing to pull for your own kind. Like Oates, he has the unmistakable impression that we watch boxing because it is “an ancient ritual.” Other sports evolve in cooperation with society. They get more complicated, more structured, and more sophisticated.

Boxing strips the accouterment away completely and stands apart from civilization, modernity and education. To drag our post-Enlightenment feelings into boxing is senseless, because boxing is lifted from a world that stands outside those feelings. If it’s acceptable to watch two men beat each other unconscious, it seems incongruous not to allow the other behaviors we’re supposed to have grown out of. We can be tribal and bloodthirsty and brutal beside the ring, because at that point we’re throwing away our veneer of culture anyhow.

In Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, the antagonist Judge Holden explains that all games try to recreate war. War is man’s natural state, he says, echoing some of the more despairing philosophers like Hobbes and his immortal description of human life as “nasty, brutish, and short.” For them, violence isn’t the broken part of the human experience. It’s the default setting.

“It makes no difference what men think of war,” Judge Holden says. “War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone.”

It endures, he says, because war is a stake of life and death and we can’t help but appreciate that it’s decided entirely through will. That’s where boxing goes beyond normal sport. Obviously, we understand boxing isn’t a death match. But the basics are so instinctive that we understand them to be from some earlier, savage contest where men decide who’s superior by violence alone.

We used to reserve the word “champion” for the best fighting man in a war host, the one who volunteered to settle the war in one-on-one combat when the interests of the tribe or polis or horde had to be enforced yearly with blood.

We’ve kept that word pure because our champions still fight our wars.

Part of the pleasure of watching boxing is watching our enemies beaten. It’s dark, but undeniable. Most boxing fans can remember their favorite fights being when a boxer they hated was bloodied and humiliated.

The canvas is our battlefield, and the champion is still our champion. We project what we hate about our enemy onto the opposing fighter; we hate our enemy’s arrogance and hope the loudmouth gets his head knocked off. Or we want our class to win, so we pull for the underdog from the wrong side of the tracks.

Boxing is a rite we take part in as spectators to pay the price of our own civilization. We know we need to see blood, we know we need to witness and participate in war and against a foe, but we know those needs go against our education. Despite the education, there’s a need for savagery. Boxers are the priests who give us that sacrament.