A constant thorn in boxing’s side since its inception has been the dissection of its health. Through centuries of prizefighting — and more than 100 years of gloved pugilism — boxing has died and has been resurrected numerous times already. But by the early 1900s, boxing had cut through the hyperbole and hammered tent stakes into the rough soil of American consciousness.

Boxing was already a very international sport, but there was something very American about a loose confederation of entities controlling most of the resources and bending whatever rules there were at the time. Also very American was boxing’s tendency to draw competitors of a wide ethnic variety.

The tradition of pitting ethnic groups against one another in the name of sport continues today across the board. In previous eras, the ethnic angle was often as much about marketing and promotion as it was about actually mobilizing demographics, but, like now, when the in-ring action was good, the skin color could be transcended. And like now, all that could crumble with the blackening of an eye.

On July 4, 1912, Ad Wolgast battled “Mexican” Joe Rivers in Los Angeles, defending his lightweight title claim in dubious fashion before a large crowd that frothed for justice before the day was through.

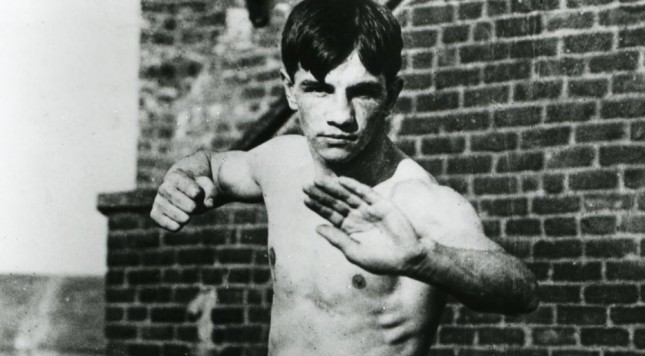

Born Adolphus Wolgast in Cadillac, Mich. in 1888, Ad was the oldest of seven children, including brothers Al and Johnny who would go on to become professional fighters. At 18, Wolgast began fighting regularly in Grand Rapids. The Grand Rapids Press, reporting before Wolgast’s second pro bout in June of 1906 said, “Young Wolgast, the other Cadillac product, who is to take part in the show, is said to be a crackerjack youngster, and he will meet a good man in Young [Eddie] Nelson, who has fought no less than twenty battles in the past six months without a defeat being registered against him.”

Wolgast wound up stopping Nelson in three rounds at Powers’ Opera House, but lost on points in a rematch a few weeks later. But in only a few months, Wolgast was an attraction in Michigan before venturing over to Wisconsin in 1907. Staying unbeaten through the first few months of 1908, Wolgast had no significant wins, save for a 1st round knockout of former featherweight contender Ole Olsen, which ended the latter’s career.

A newspaper loss to Owen Moran in New York did little to derail Wolgast, as Moran had just fought to a draw with featherweight champion Abe Attell at promoter James Coffroth’s Arena in Colma, Calif. a few months prior. After scoring two draws in Racine, Wis., Wolgast took his show to California with a (42-2-8, 18 KO) record.

Three wins in or near Los Angeles — where it had become illegal to schedule fights for longer than 10 rounds or render decisions — landed Wolgast a shot at Attell in a non-title bout. A 10 round draw later, and Wolgast had boosted his credentials considerably, and picked up manager Tom Jones.

In 1909, Wolgast fought his way to a fight with lightweight champion Battling Nelson in another non-title bout in L.A. After handing Nelson what the Los Angeles Herald called a “thorough beating,” the demand for Wolgast to challenge for some manner of title was sky high.

Wolgast went east, then fought his way back to California, where he was matched against Nelson in February of 1910, just outside of San Francisco. And this time Nelson’s title was on the line.

Nelson and Wolgast pushed one another to the 40th round in a hellish affair. Both men had been rocked and bloodied, and Wolgast touched the canvas in the 22nd. But referee Eddie Smith was forced to save Nelson from himself, as the comically tough character refused to submit.

The new lightweight champion traveled to San Francisco, the party center of the West Coast, and relished his new-found fame and attention. But as the champion, business called, and in June, Wolgast was back in the ring.

What should have been a routine warm up against Jack Redmond in Milwaukee actually weighed heavily on Wolgast’s career; at some point during their bout, Wolgast suffered a freak arm injury. After taking two months off, Wolgast jumped back in with a newspaper win, but a September meeting with Tommy McFarland in Fon Du Lac, Wisc. ended with Wolgast earning a difficult newspaper decision and walking away with his left arm fractured directly below the elbow.

Four months away from the ring had Wolgast, press and fans alike anxious for a title defense, and Wolgast returned in 1911, losing two newspaper decisions to Knockout Brown in two difference cities. Before March was up, Wolgast made two defenses in Califonia. April saw Wolgast taking out One Round Hogan in two, and another defense in May came over Oakland Frankie Burns.

On the Fourth of July, 1911, Wolgast defended his belt once more, but this time against an old foe: former conqueror Owen Moran. After 10 rounds of solid action, the champion took a few rounds off for no apparent reason. But at the start of round 13, Wolgast attacked Moran, landing a number of punches downstairs before the Briton began to slowly sink to the canvas. As he slid down, Wolgast landed a right hand that essentially put Moran out. In a heap, Moran attempted to plead his case that he had been hit low, but he was counted out.

Little attention was paid to Moran’s claims of foul, and again the champion reveled in his fame.

As Wolgast was in training to face future lightweight champion Freddie Welsh in Colorado, however, a bout of appendicitis struck Wolgast, who was forced to be carted to the hospital for an emergency surgery, and then ordered to stay out of action for a number of months.

In early May, after being sidelined for what seemed like a decade, an article in the Denver Post written by H.M. Walker — who would later become a prolific screenwriter — wore the title, “Joe Rivers Greatest Boxer Mexico Has Ever Produced.” Walker went on to say, “A couple of years ago Joe had to make a weekly fight to slide his fork through enough red beans to satisfy his healthy appetite. Now Joe wears diamonds as big as cranberries, owns two automobiles and has real estate holdings scattered all over Los Angeles county. Rivers pugilistic record speaks for itself. He is, by far, the best boxer California has produced since the afternoon when Jim Corbett added up his last column of figures and told the bank people to hire another mule. Joe is matched to box Ad Wolgast at Venon on next July 4 for the lightweight championship of the world. The Mexican flag will be tied around the top rope in his corner and if the little bronze boy lives up to his friends’ expectations, it is going to be an interesting day for the gringos, Wolgast and [Tom] Jones.”

Los Angeles birthed Mexican Joe Rivers in 1892, though he went by the name of Jose Ybarra then. A fourth-generation Californian, Rivers happened to be passing by Al Greenwald’s Cigar Store as great L.A. promoter Tom McCarey stressed himself up and down the street, in need of an opponent for Max “Young” Webber the following evening. As the story was told in a press release prior to Wolgast-Rivers I, Rivers either heard or saw McCarey worrying, and volunteered himself for the job at just 15-years-old. When McCarey asked a few locals about the kid, they told him they’d seen Rivers staging street fights prior to club shows outside local venues, and that the kid was tough and could punch.

McCarey took Rivers under his wing and gave him an accessible name, waiting for Rivers to turn 18 to press forward with his professional career. In 1910, Rivers rattled off five wins, and the following year his opposition rose sharply when he picked up manager Joe Levy, and Rivers went 1-1 against Johnny Kilbane, who was months away from becoming featherweight champion. The loss, however, was a knockout that seemed to stay with Rivers in the press until his next defeat, when coupled with a few other flash knockdowns suffered.

Rivers had a good thing going in Vernon, Calif., though, and fought to a draw in 20 rounds with former bantamweight champion Frankie Conley to close out 1911. Then on the first day of 1912, Rivers got revenge over Conley and stopped him in 11 rounds. The Boston Herald said of the fight, “Conley constantly carried the fight to his opponent, only to receive the worst beating of his ring career.”

In March, Rivers easily vanquished fringe contender Jack White, bringing his record to (15-1-2, 10 KO), and putting himself in line to challenge Wolgast for his title claim.

Wolgast, it seemed, was getting big for his britches despite his appendicitis operation. A news wire from Los Angeles reported that during a meeting with promoter Tom McCarey, Wolgast had pinned a huge diamond on the front of his coat and walked with an expensive cane. His promoter Tom Jones cracked, “We will make any weight for this bird Rivers from 122 up and let him name the weight. We are going to work on the Fourth of July and we would rather work here than any other place. We would like to get Rivers, as it would be a great contest, but Rivers is only one of a half dozen challenges.”

Not to be outdone, during pre-fight promotion, Levy introduced his charge to everyone as “the next lightweight champion of the world.”

Moving past the outward confidence, Wolgast still fully intended to take a few shorter fights to ready himself for serious milling once more. In early May, he tangled with Willie Ritchie at Coffroth’s Arena, knocking his future nemesis down twice before being rocked multiple times and out-boxed for the rest of the four rounds. Immediately afterward, he told reporters, “What I need is five or six of these short-route fights before I take on Joe Rivers on the Fourth of July. I have not noticed any ill effects from the operation I underwent in Los Angeles. The test with Ritchie shows I am in good shape in the mid-section.”

Refusing to stay idle, Rivers performed in paid sparring exhibitions against Babe Davis, one of his chief training partners, and Willie Canole. Rivers said he had been offered a lot of money to tour the vaudeville circuit, but the exhibitions paid similarly and kept him in better shape. The shows weren’t particularly well-received, however, as the San Francisco crowd on hand for his May 3 exhibition against Davis grew bored, and some asked for their money back.

On the last day of May, Wolgast won a newspaper decision from Young Jack O’Brien amid fears he would be pulling out of the match up due to a back injury. Meanwhile, elsewhere in the U.S., multiple newspapers noted the disinterest in Jack Johnson’s upcoming defense of the heavyweight title against “Fireman” Jim Flynn in favor of Wolgast-Rivers.

Rivers set up training camp at Shaw’s Gymnasium in Venice, while Wolgast went to Wheeler Springs for a week or two in order to be outdoors, per his team. It may have just been propaganda, but reports out of Wolgast’s camp stated that he had worn out one of his Stag Hounds, who was so tired from Wolgast’s training, he refused to do road work with the champion anymore.

Wolgast sparred regularly with Pete McVeigh and Kid Dalton upon returning to the city and setting up camp in Vernon, where the fight was schedule to take place. In mid-June, odds were reported as 10-to-9 in favor of Wolgast, and a few days later, the odds had slid toward Wolgast even more at 10-to-6.

H.M. Walker, who was on hand in Wolgast’s training camp for the Denver Post, noted the week of the fight that Wolgast had been going full speed in the gym, demanding that his training partners and sparring partners not take it easy on him. Walker said, “Ad’s recent mountaineering, to all appearances, has improved his physical condition in more ways than one. His mind, judging my yesterday’s workout–his first real entrance upon his training for his Fourth of July go with Mexican Joe Rivers–is improved. His stamina, which it was feared had received a severe setback through the operation for appendicitis last winter, has undoubtedly improved, and the trip added five pounds to his weight.”

But a few days later, Wolgast worked out before a crowd of approximately 3,000 people at promoter Doyle’s training facility, looking none too impressive, per the Riverside Independent Enterprise. Wolgast then retired to vaudeville actor Nat Goodwin’s ranch to finish much of his training. In the days before the bout, in fact, media focused on the fact that Wolgast was actually underweight for the bout by almost 10 pounds.

Attention shifted away from Wolgast’s weight when both fighters’ training camps cooled down, and at least one media member was quick to point out that Rivers wasn’t exactly a veteran in the lightweight division, himself. Also aiding in distracting press from asking Wolgast fitness questions was the battle over who would be the third man in the ring. Wolgast and Jones suggested San Francisco referee Jack Welsh, who had refereed four of Wolgast’s previous bouts, while a more neutral arbiter in James Jeffries was sought by Rivers’ camp. When Jeffries declared he couldn’t participate as he knew both fighters too well, Rivers settled on Welsh, which would prove to be a serious error.

Hobo Dougherty, a featherweight out of Wisconsin, was befriended by Wolgast early in the latter’s career. As Dougherty told it, Wolgast was kind enough to donate a quarter to the Hobo’s next meal or two, as the nickname was literal at the time. Dougherty was asked whether or not Wolgast was healthy the day before the bout, and he replied, “Ad is faster and stronger than he was before the operation. I don’t know who could know better than me.”

Wolgast said going into the fight, “I will down Rivers–then let the rest of the bunch look out.”

Rivers remarked, “Wolgast might run into a surprise party that will make him heart sore.”

The toll of a bell set Wolgast and Rivers upon one another, and the two men “fought like catamounts,” as one news wire wrote, matching the later Fourth of July festivities. But the same news wire said of round 1, “Rivers was much faster and his blocking was better than that of the champion.” Rivers was pushing the fight early, and Wolgast was keeping up, but not getting the better.

A one-round lead bled into carnage in round 2, as Rivers was seemingly unable to miss, and a cut strangely opened up near Wolgast’s neck that was spurting blood. Before the round was over, Wolgast’s nose had also sprung a serious leak. But Wolgast came roaring back in the 3rd, exchanging with Rivers and covering the challenger with crimson in the clinch, though Rivers’ opened up the wound on Wolgast’s neck further when the two tussled on the inside.

The Grand Rapids Press, reporting from about 100 miles outside of Wolgast’s hometown, said, “During the early rounds Rivers led by a wide margin, Wolgast seeming to have planned to let his opponent tire himself out, not really beginning to fight like he has in the past until after the sixth round.”

Wolgast’s timing was off when Rivers fought from the outside, and the challenger was tagging Wolgast before falling in and mugging. Through round 6, Wolgast was stunned a few times and had a shade in perhaps one round, and it was debatable. And in round 6, a right hand inside floored Wolgast, who bounced up immediately, but was trailing badly.

Round 7 saw Wolgast pushing the envelope with body shots — some legal, some not — and finally getting to Rivers, who slowed and looked to clinch after rocking Wolgast again. In the 8th, Rivers’ defense turned to flight, and Wolgast attempted wild rushed to punish Rivers about the body and slow him down, which worked.

Slower action marked the 9th, though Rivers a few times targeted the area where Wolgast’s appendectomy scar lived, which summoned forth more body work from the latter that likely stole the round. And the 10th continued with Rivers trying to keep away and win from the outside, but Wolgast was rushing in to interrupt any possibly rhythm to be had. To make matters worse for Rivers, his defense had largely become simply covering up, as Wolgast was gaining steam in the clinch, and the Californian’s legs were weakening.

There were still some surprises from Rivers, though, and a round-by-round recap via news wire said of round 11, “Rivers seemed to force the fighting. Wolgast could not hit him hard and clinched. Rivers then stood still and took four or five hard lefts and rights to the jaw but never winced. He then sent in a hard left staggering the champion. Wolgast’s smile had disappeared, and he seemed very tired.”

Aggression from Wolgast had become highly flawed, and Rivers’ simple covering up was proving sufficient to avoid most punishment. Wolgast couldn’t break through.

The men began mixing up again in round 13, though Rivers had retreated to the ropes during the round a few times. In the final sequence, Wolgast backed Rivers to the ropes, and per most reports, caught Rivers with a left hook to the cup. Nearly simultaneously, Wolgast took a right hand that leveled the champion. As both men fell at the same time, referee Welsh appeared confused and briefly looked to ringside officials for guidance, ignoring River’s plea that he had been hit low, and very hard. Welsh walked over to Wolgast, who was all but dead weight, and helped dragged him to his corner, declaring Wolgast the winner.

Owen R. Bird of the Los Angeles Times wrote of the fascinating result, “The pace had been ferocious from the opening bell and toward the end of the 13th the fury was redoubled. Then this thing happened. Both fighters suddenly lay writhing on the floor together, almost in a heap. The referee seemed to be trying to count out Rivers, and help Ad Wolgast to his feet in a confused sort of way. Rivers had apparently been fouled, but after a moment’s hesitation, the referee began to count over him. It took Jack Welch eight seconds to count out Rivers, after he had been fouled, and render a decision, besides helping the fallen champion to his feet. The gong rang as he finished the downward stroke of the five count. As for the fight–there never was a better one in the Vernon area.”

Trainer at the Los Angeles Athletic Club, De Witt Van Court, said, also via the Los Angeles Times, “I saw Wolgast hit Rivers a hard left-hand in the groin as plain as I ever saw anything… I believe Rivers had hit him square in the stomach and knocked his wind out. I also believe Rivers was entitled to the decision on a foul.”

An uproar from ringside spilled into the ring, with River’s corner and supporters threatening to set chaos loose. Welsh wisely fled. Both fighters claimed to have been fouled: Rivers with the low blow, and Wolgast said he had taken a knee to the head when Rivers went down and pulled Wolgast down with him. Rivers and his team infamously produced a badly dented metal foul protector as evidence, which caught on as a news item.

Editor of the San Francisco Chronicle, Harry B. Smith, wrote from ringside, “Wolgast’s victory was a hollow one save for that he retained the all-precious title. His reputation is torn to tatters and it is safe to say the next time he steps into a ring with a foe worthy of him there will be no two to one offered by his backers.”

The Denver Post said, “The public, the one means of support of the fight game, received another wallop at Los Angeles yesterday afternoon when referee Welch (sic) gave Ad Wolgast the decision over Joe Rivers. In giving Wolgast the verdict Welch plainly showed that he is either incompetent or that Rivers was jobbed.”

Countering much of the negative press and cries of a fix or botched verdict, however, was none other than H.M. Walker. He said, “Up to the sensational finale the battle had been one of the most ferocious ever staged in southern California. Wolgast had proved to be the Wolgast of old. No longer the specter of the appendicitis operation hung over him. Trained to physical perfection, he was fighting like a wounded tiger, had punched and hooked Rivers’ nose and eyes until his features were unlovely to look upon and had beaten Joe about the body until he was weak. Rivers could scarcely have lasted the limit of twenty rounds. … Many take issue with me, but I sincerely believe that Wolgast has established his supremacy over the Mexican. The thirteenth round confusion was caused by Referee Welch completely losing his bearings.”

Former fighter Harry Gilmore said via news wire from Chicago, “It was anything but robbery, Welch is a courageous referee and while the mixup was a confusing one he did not hesitate in counting the Mexican boy out the second he dropped from the blow. While openly admitting that the blow landing right on the belt line, with a fraction of the glove showing low, it was not sufficient to be characterized a foul and the real force of the punch was felt above. Up to the thirteenth and final round Wolgast was a decided winner and had his plucky opponent badly banged up, with the betting questionable whether or not Rivers would last the fifteen rounds. It was undoubtedly one of the best and most terrific lightweight battles that the coast has seen while it lasted and though Rivers failed in his aspirations to becomed the champion he will be great in his defeat, for he fought desperately and as savagely as a wildcat until the champion had calmed him down after the seventh round.”

It was reported that Wolgast took home about $40,000, and had a deal for 50 percent of the film rights and the same percentage of the gate.

Two days after the fight, photos sent to various newspapers seemed to only deepen the mystery, as they showed Wolgast landing two left hands to the belt line, and both fighters collapsing near the ropes, then sprawled out and groggy as Welsh mostly looked on, squinting into the sun. And in hindsight, Welsh’s involvement with both the Moran bout and the Rivers debacle, and the fact that both were on the Fourth of July, was strange, to put it kindly.

According to an 80th anniversary article in the Los Angeles Times by Earl Gustkey, film of the bout showed that the left hand from Wolgast was clearly low, but how and why Wolgast went down the way he did wasn’t clear.

Wolgast would lose four more times by disqualification, and in at least two other bouts, an opponent of his claimed to have been hit low at a crucial point in the fight. The November following the first Rivers encounter had Wolgast losing the lightweight title by DQ to previous foe Ritchie, who again defeated the former champion in 1914. A draw with Rivers in 1914 followed by a stoppage of Rudy Unholz were Wolgast’s final flurries as a serious fighter. He couldn’t manage to defeat an upper level fighter ever again, and retired after his only fight in 1920.

Boxing had already sunk its teeth in and was tearing off chunks, as Wolgast suffered a “nervous breakdown” in 1917 and was declared mentally incompetent by a Milwaukee court. Wolgast went through the Wisconsin system, and was then transferred to the Stockton State Prison’s psychiatric ward, where he was reportedly beaten mercilessly on more than one occasion by guards who wanted to test their mettle against a former champion.

Years of health problems and mental decline plagued Wolgast, who was in hospitals or institutions more than he wasn’t. In 1955, the former lightweight champion of the world succumbed to pneumonia and lingering heart issues and passed away at 67-years-old in a state hospital.

On the Fourth of July in 1913, Rivers was again stopped for the lightweight title, but this time by Ritchie, and legitimately. Rivers faced Freddie Welsh, Johnny Dundee, Frankie Callahan, Johnny Griffiths and Willie Hoppe, unable to defeat any of them. As 1917 came to a close, Rivers’ loss column became overpopulated, and his opposition became much weaker. From 1920 to 1924, Rivers fought up and down the West Coast, unable to revive his career, and he retired at 32. However, his first bout against Dundee is said to have been the last 20 round bout in California before fights could legally be just four rounds, for a decade.

As years went by, Rivers largely stayed out of the spotlight, though the famous “double knockout fight” between he and Wolgast lived on, occasionally cited by sports writers in need of odd facts to add to their columns. There were various false reports of Rivers passing away, oddly, but in 1957, Rivers found himself in the Los Angeles County General Hospital with an unknown ailment, before he was transferred to the Inglewood Sanitarium, where he died of a cerebral hemmhorage at 65.

The supreme irony is that the sport that made both Ad Wolgast and Joe Rivers was constantly pointing to both of them as reasons why the sport should no longer be. Wolgast’s physical deterioration was very public, while Rivers’ health issues were only widely known at the end. Nonetheless, aside from being the subjects of sporting factoids, they were both also used as cautionary tales.

California succeeded in stamping out lengthy bouts in professional boxing, but only temporarily. History remembers Wolgast-Rivers I in a skewed manner, but that it’s remembered at all is about as important.

(Photo via)