Are we sure this kid isn’t Kazakh?

The thought dawned on me the first time watching Naoya Inoue. It might have been his swarming stoppage of Adrian Hernandez to win a junior flyweight title. Or maybe when he hopped a weight class to turn Omar Narvaez’s liver into pâté and swipe his belt. Could have been his first U.S. appearance, when Inoue took apart Antonio Nieves brick by brick. The when, though, is sort of irrelevant. I just remember the feeling.

From that first moment — and likely before — his international fame gathered into a groundswell, Inoue projected something that wasn’t quantifiable, an air that couldn’t quite be explained. It was a blend of confidence, menace and giving not a single shit who might stand before him. A spritely, hair-dyed 26-year-old from Yokohama, Japan, Inoue could pass for the pretty one in a teenage K-Pop band. But his aura in the ring manifests as the overlap of some twisted Venn diagram — part medieval executioner, part slasher-film clown. A thousand fighters before Inoue strained to achieve that threshold of professional sociopathy, but only a few did more than wear its trappings like a rented suit. In recent years, just one truly owned it: Gennady Golovkin.

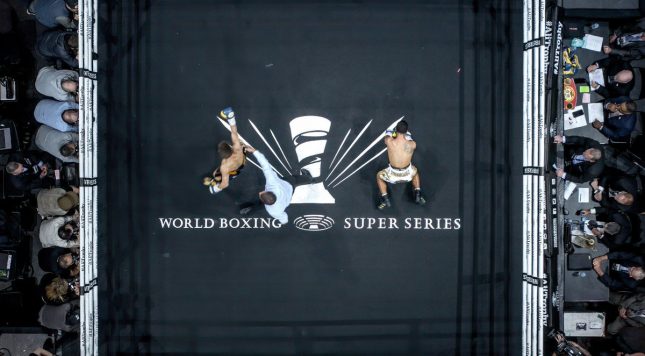

My first glimpse of Golovkin — the Kazakh good boy, the smiling destroyer of worlds and successor to holy terrors Tyson, Duran, Foreman and Liston — gave me the same chicken-skin thrill I received when I was introduced to Inoue. I felt it again on Saturday when I watched Emmanuel Rodriguez straighten his back and dig in his boots against Inoue for a round in Glasgow on DAZN, then visibly crumble when, moments later, “The Monster” materialized to snatch his soul.

That’s worth lingering on for a sec: Rodriguez (19-1, 12 KOs) is no taxi driver. He entered Saturday’s unification fight — a semifinal bout in the World Boxing Super Series bantamweight tournament — an undefeated and respected titlist from Puerto Rico flirting with the division’s top five. But Inoue (18-0, 16 KOs) is another animal altogether.

It starts, of course, with his power. Inoue’s is transformative, scrambling his foes’ wits and liquefying their will into stark terror. Rodriguez, to his credit, was game — and his quickness and willingness to trade allowed him to give nearly as good as he got for the first three minutes. But it was all downhill — steeply — from there. Inoue immediately calibrated his weapons systems for Round 2, landing atomic right hands – these more flush than those in the first — over Rodriguez’s guard. When Inoue, 30 seconds into the round, drilled a right hand to the gut to set up a scything short left hook that mashed Rodriguez’s face and dropped him where he stood, he gave a little fist-pump and dutifully bounded away to his corner. Inoue knew: It wasn’t over — but it was over.

Rodriguez, nose bloodied, rose gingerly and gave it a go, mindful of Inoue diving in with a lead right hand when the action resumed. What Rodriguez missed was the left hand follow-up digging to his liver — a shot that left him with an agony-contorted face only Edvard Munch could love.

From the mat, Rodriguez, grimacing and squint-eyed, shook his head assuredly in the direction of his corner. If his team was giving him an out, hoping to spare him more damage, Rodriguez wasn’t taking. He was on his feet again, but when Inoue pounced with a four-punch flurry that bowled over Rodriguez for a third knockdown, the decision was made for the Puerto Rican fighter: Rodriguez was up by Michael Alexander’s count of eight, but the referee had seen enough to stop it.

Inoue will have more significant challenges ahead, including a meeting with the rejuvenated(?) Nonito Donaire in the tournament final, probably before the year is out. It’s unlikely he’ll continue bounding through divisions, especially while the depth at 112 pounds can keep Inoue busy with legitimate competition. But in the meantime, it’s moments like Saturday — a generational fighter laying bare the gap between his opponents’ earthbound talent and his own boxing galaxy brain — that remind us why we watch in the first place.

In a different sort of spectacle set in Glasgow, Josh Taylor (15-0, 12 KOs) outworked Ivan Baranchyk (19-1, 12 KOs) in the WBSS 140-pound semifinals, in a performance that teetered between virtuoso and vainglorious. Taylor bounced, shifted, fired at angles and occasionally flew too close to the sun in outpointing Baranchyk, advancing to the tournament final via unanimous decision, 117-109 and 115-111 (twice).

Taylor, a Scotsman and an odd duck of a fighter, was cheered wildly inside the SSE Hydro — and it’s possible that both contributed to his popularity. Rangy, active and borderline balletic for a 5-foot-10 junior welterweight, Taylor conjures wizardry where Inoue marshals blunt-force trauma on an industrial scale. In its way, though, Taylor’s brand is just as impressive.

Because Baranchyk can be relatively sloppy and predictable, slinging long, looping hammers with little regard for the jab or a sounds defensive plan, he set up nicely for Taylor. Then again, no one likes being hit in the goddamn face with a sledgehammer — least of all one swung by a baby-faced Belarusian who appears to be in the grips of a Cross-Fit addiction. Taylor would still need to mind his p’s and q’s.

And he did, for the most part: After a roughly even first round, Taylor began piling up scoring shots — working the body, countering Baranchyk’s wild offerings and staying on the move to not only avoid danger but also set up his own attack. An argument could be made that Taylor won every round leading up to the sixth, when, after the action had slowed, the Scotsman floored Baranchyk with a stunner of a counter right hand. Baranchyk beat the count, but Taylor went right back to work, muscling him down again with a blitz punctuated by a straight left.

Baranchyk popped up, survived the round and, presumably fueled by a cocktail of mescaline and Tasmanian Devil’s blood, came roaring back in the seventh. Taylor who had so deftly parried or blocked most of The Beast’s best shots in the first half of the fight, was slower to step out of the line of fire — or skipped it altogether. Taylor’s friend and countryman, Carl Frampton, voiced his concern at the tactical change, and with Taylor nursing a cut over his left eye and staggering ever-so-slightly after one Baranchyk power shot in the 11th, it wasn’t hard to see Frampton’s point.

Taylor, may the gods bless him, essentially told his pal to take the proverbial piss. He unloaded in the final round, hopping on the back foot just often enough to avoid the most dangerous bits of Baranchyk’s own last, desperate assault. The Scotsman steered clear of potential disaster, and with that done, the scorecards were never in doubt. “Ee-zay, pee-zay!” was how Taylor described the win in the postfight interview. It most certainly was not. But that was likely Taylor, grinning as he spoke, taking a piss himself.

(Naoya Inoue, left, Emmanuel Rodriguez, right; via)