Before Germany’s national soccer team finally kicked off the 2006 World Cup on its home soil, the country’s concerns about its Mannschaft had grown grave. So-called reforms had changed a great deal about the way the program ran, the way the team was set up, its hierarchy and structure, its everything.

Talismanic goalkeeper and captain Oliver Kahn had been benched. American fitness specialists had been brought in, to the horror of the locals who fancied themselves world leaders in that field. The results were shaky and the play often ragged. A process was supposed to be underway, but the people had no patience for it.

The totally inexperienced manager, Jurgen Klinsmann, had only gotten the job because absolutely nobody else who was actually qualified wanted it after the disaster that was Euro 2004 for Germany. So he’d negotiated a lot of freedom and leverage. He would get to do things his way. But almost two years in, ahead of the big World Cup on home soil, a branding exercise for Germany at large as a modern and welcoming country, tolerance for Klinsmann and his ways was threadbare.

Less than three months before the tournament, Klinsmann was reportedly a single loss away from being fired. His side had been hammered 4-1 in a March friendly against Italy. And had another friendly later that month with the United States – ironically – been blown, the German federation would have gone into damage-control mode before the World Cup had even begun. Germany won at a canter, also by 4-1.

What happened next is well established. Germany’s rejuvenation finally took hold and it played far better than its fans dared hope once the big tournament finally rolled around. They were eliminated in the 119th minute of extra time in the semifinals against Italy, who would be world champions. The fans were so enamored by their team that patriotism finally became socially acceptable in Germany again, some six decades after the last you-know-what.

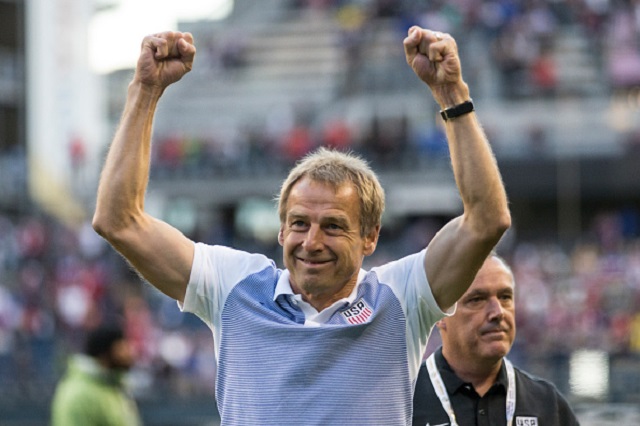

Klinsmann, who had been criticized and derided for almost the entirety of his two years in charge, was begged to stay on. By the federation and by the press, which had once waged open warfare on him. Exhausted, he left anyway, with Germany’s highest federal decoration, the Order of Merit.

A decade later, he was in much the same position with the United States, albeit on a smaller scale. Ahead of the one-off Copa America Centenario on home soil, the angst over his methods had built to a fever pitch. He’d been in the job for almost five years by that point – and had doubled as the technical director for a few years as well. Of all the tall promises, few had materialized. Both the senior and youth national teams had arguably regressed on his watch, in spite of his enormous salary – estimated at $3 million a year, about four times that of his predecessor, Bob Bradley.

The U.S., it seemed, was going nowhere. And when it got yet another tough draw for the Copa – after being dumped into the Group of Death at the 2014 World Cup, which the U.S. did survive – things looked bleak. Maybe staving off embarrassment was the best the Yanks could hope for.

Colombia made quick work of them in their first game, winning 2-0. One more loss, U.S. Soccer president Sunil Gulati seemed to be telling the press between the lines, and Klinsmann might very well be out of a job.

But then followed an emphatic 4-0 win over Costa Rica. A narrow 1-0 against Paraguay – down a man. And, at length, Thursday’s cathartic 2-1 win over Ecuador to reach the semifinals, Klinsmann’s seemingly fanciful target for the tournament.

That @clint_dempsey goal 🔥🔥🔥 #USAvECUhttps://t.co/Va7IFDSto7

— Seattle Sounders FC (@SoundersFC) June 17, 2016

Suddenly, things are clicking. If the last two results were ground out following an ejection, the level of the Americans’ play has been of such a markedly improved caliber – even when they’re merely trying to lock up a result – that it feels like a sea change.

Ten summers after finally thriving and being embraced by Germany, Klinsmann is living through much the same thing with the United States.

“Our program is maturing. Our players are maturing,” Klinsmann told reporters following the quarterfinals win. “They are learning with every game they can play in this type of an environment.”

“Right now this team, I think they’re more convinced, more confident,” Klinsmann continued. “But they are also growing and maturing. They pushed them [Ecuador] back, they made them work also defensively and that’s another step forward from two years ago. We pushed the game back into the other half, and make them work the same way as well. It’s cool, then you have the feeling, ‘We can go eye-to-eye here.’”

Gyasi Zardes, off the feed from Clint Dempsey, gives the #USMNT some breathing room. #USAvECU #MyCopaColors https://t.co/SxKajJCeJS

— FOX Soccer (@FOXSoccer) June 17, 2016

The hoped-for stylistic revolution hasn’t quite arrived. The Americans aren’t commanding games against world powers yet. But they at least look comfortable and confident on the ball now. They really do take the game to the opponent when given the chance, just as Klinsmann had been imploring them to for half a decade, even though it mostly rang hollow.

“They are getting just more and more of those messages,” Klinsmann said. “They understand what the next level up there is about.”

In a breakout tournament, the Americans have come to understand a lot of things. It has taken Klinsmann more than twice as long to turn things around as it did with Germany, but then he had a more expansive job on his hands with this team.

At long last, the Klinsmann experiment is beginning to pay dividends and make sense. It seems like he may once again be vindicated in the end.