Sneaking into major sporting events is a lot easier than you might think. Yes, even the one Sunday in Atlanta.

I’ve done it more than 30 times, including at the Super Bowl, World Series, The Masters, and a Wimbledon final. I detail the stories in my book, Ticketless, that was just released.

But the story really begins at Scottrade (now Enterprise) Center in St. Louis, where I was an usher and ticket taker during high school. I learned that those mean-looking security guards at the stadium doors are more concerned with trying to prevent weapons and alcohol from entering the building than people without tickets.

I learned that those ticket takers with their scanners at the ready have been standing on concrete floors for two hours, the wind blowing in from the constantly opening doors has made their fingertips numb, and they’re making minimum wage.

And I’ve done a lot of research into the history of gatecrashing. As I see it, there are three main techniques for sneaking into sporting events — any one of which could (and probably will) be used in the hours leading up to Rams-Patriots on Feb. 3.

1. Convince security you belong inside — without a ticket (or with a fake one).

We’ve probably all heard stories of folks handing ticket stubs or wristbands through a gate, to their friends on the outside. Fairly standard. But the guy who made a fake press pass to get into Game 7 of the NBA Finals? Next-level.

There’s also Scott Kerman, who snuck into the 1993 Super Bowl by asking a hot dog vendor in the employee parking lot before the game, “Who’s your boss?”

The boss was named Vince. Kerman then told a different vendor, “Tell Vince that Scott Kerman needs to see him.”

The harried boss came over and Kerman told him, “I’ve been trying to reach you all week about work.“

“Ever served coffee?” was the response. When Kerman said yes, Vince called out to a security guard, “Let this guy in.”

Then, there’s the old tried and true: wear your Sunday best, show up at the media entrance of just about any arena or stadium in the country, and say, “I’m here to see [So and So, Vice President of Corporate Partnerships].”

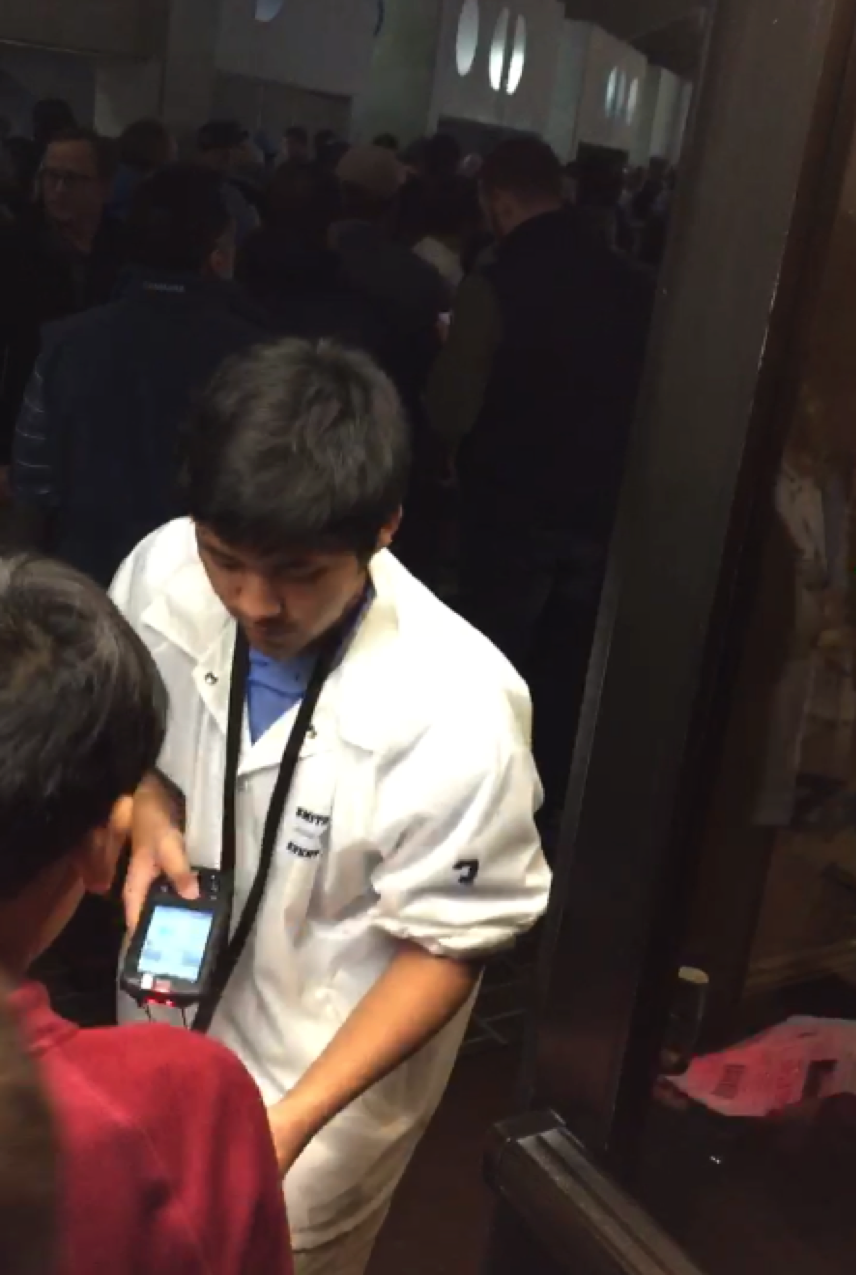

My story with this method: Before Duke-UNC, Feb. 18, 2015, I emerged from the tunnel beneath Cameron Indoor Stadium and climbed the stairs. This gentleman was standing there, but I just nodded at him like I knew what I was doing and walked through those doors. I wound up courtside.

2. Literally sneak in.

Before a game, thousands of people are jostling in poorly organized lines to pass through metal detectors, recollect their wallets and phones, find their tickets, have them scanned, and enter the arena or stadium. It’s chaos.

One of the all-time great sports gatecrashers, One Eye Connelly, used this tactic often in the early 20th century.

As I wrote here: “On June 12, 1930, before the Jack Sharkey-Max Schmeling bout at Yankee Stadium, One Eye simply ‘Passed through the turnstile at the height of the rush with a party of six men.’ When the ticket taker asked the men about their seventh ticket, One Eye slinked away. The gatecrasher, probably overwhelmed, ‘dropped the issue in favor of handling the crowd.’”

There’s another tactic that falls into this category. During the first round of the NCAA Tournament in Buffalo in 2010, my two favorite teams, Missouri and Gonzaga, were playing — Mizzou in the afternoon session, and Gonzaga in the evening. Supposedly, you needed separate tickets for the two sessions.

But after Mizzou’s game, while arena staff were clearing fans from the building, a friend and I went to the upper level, pulled back a curtain, and jumped into a garbage bin. About forty-five minutes later, when fans started to enter for the second session, we hopped out.

3. Spin-move. That is, run right in.

To ‘spin-move’ is a term I invented, although I must admit: it’s not exactly rocket science. And you don’t actually have to spin.

The next time you go to a sporting event, take a look at the concourse behind the ticket takers. Maybe there’s a security supervisor. Maybe a few uniformed (though they’re likely off-duty) police officers. More likely, there’s nothing but hundreds of fans dressed in the home team’s colors walking every which way.

There is virtually nothing stopping you from running past the ticket taker and getting lost in the crowd. Even turnstiles, which theoretically would slow you down, have become a thing of the past; most modern venues don’t use them.

I do not recommend getting into the gatecrashing business unless you really do your homework. That will involve studying building layouts, and above all, going to lots of games with tickets to understand how the ticket-taking process works.

But it can be done. And if history is any guide, it will be done at the Super Bowl: North America’s premier sporting event, and premier gatecrashing event.

Trevor Kraus is the author of Ticketless: How Sneaking Into The Super Bowl And Everything Else (Almost) Held My Life Together.