The Tampa Bay Buccaneers almost pulled off an incredible comeback against the Los Angeles Rams in the divisional round of the NFL playoffs Sunday, coming back from trailing 27-3 in the third quarter to tie the game at 27 with 42 seconds left (aided by three Rams’ fumbles and other miscues in that span). However, the Rams then executed a great final drive of their own: Matthew Stafford got sacked on their first play, but a timeout let them reset, and Stafford then found Cooper Kupp for 20, Kupp got out of bounds, and Stafford then found Kupp again for 44, managed to spike the ball to stop the clock, and Matt Gay hit a 30-yard field goal to give Los Angeles the 30-27 win.

There’s plenty to talk about after that one, but one of the most interesting late-game moments came on that final Bucs’ touchdown, a nine-yard rush from Leonard Fournette on fourth and one. Was it the correct move for Fournette to score there, or should he have gone down at the goal line and let them kill more clock before punching it in?

There’s obviously some logic to the Bucs just taking that game-tying touchdown on that play rather than gambling they could get it later with less time remaining. Even going down inside the one does not a sure thing make. And 42 seconds on the clock is not a ton of time for a drive into field-goal range; the Rams needed a remarkable drive to make that work. (They also only got those 42 seconds because Los Angeles head coach Sean McVay called a timeout before the fourth-and-one play.) But both of these options carry some risk; the question is which is riskier. And while we can’t know exactly what would have happened in this particular situation if the Bucs had chosen the other option, we can look at similar plays over time.

Let’s start with a search at Pro Football Reference’s Stathead PlayFinder. The specific circumstances here are a little complicated because it’s uncertain exactly how many further shots at the end zone the Bucs would have had if Fournette had gone down inside the 1. It’s also hard to replicate exactly how the play would have looked, as inches to gain is easier than a full yard to gain, but NFL box scores are tracked by full yards. But we can get an idea of what this might have looked like by running a search for criteria “From 1994 to 2021, any team, in the regular season, play type is pass or rush, at Opp 1, on 4th down, sorted by yards descending.” (The reason for limiting this to fourth downs is that on any other down, there’s a possible outcome of “another play,” which isn’t really useful here. We’ll discuss the factor of multiple plays in a moment.)

That produces 709 tracked plays, including 237 passes and 472 rushes, and 373 touchdowns. That’s a touchdown rate of 52.6 percent, which is not great. But it’s certainly easy to imagine that the actual success rate here would be higher, as the Bucs should have gotten at least two shots at it, and they wouldn’t have had a full yard to go.

If we give them two full shots at it, that’s dependent probability. The probability of scoring on the first play is 52.6 percent, the probability of no score on the first play and a score on the second play is 0.526*0.474 = 24.9 percent, so the combined probability of a score on either of the two is 77.5 percent; that’s closer to what the odds seem like here, and it’s easier to imagine the real odds being even better with only inches to go. But while it’s not exact, the data here is useful for indicating that the short-yardage goal-to-go play doesn’t always work.

By the way, if we switch this to just rushes, we get 259 touchdowns on 472 rushes, 54.8 percent. And if we generalize “fourth and one from the one” to “fourth and one anywhere,” a Yale Undergraduate Sports Analytics Group study by Evan Green and Michael Menz in 2015 found 3181 plays since the 1994 season, converted at a 65.7 percent rate. However, fourth and one anywhere seems easier for the offense, as the defense has to at least ponder the idea of a downfield shot. That’s not the case for fourth and one from near the goal.

A similar discussion here came up a lot in 2015 around the Seahawks not handing the ball to Marshawn Lynch at the end of Super Bowl XLIX. There was talk around that on a ton of fronts, from the Patriots’ defensive alignment to the passing play Seattle ran. But maybe the most interesting discussion was how Lynch converted 20 of 28 fourth-and-ones from anywhere that season, but just one of five carries from the one, and was one for two in one-to-go situations from anywhere that game. That adds to the case that a short run isn’t guaranteed, even with a top back.

As for the Rams, we can get a general idea of how unlikely their drive was from NFLFastR’s expected points calculator example on drives starting after a touchback. In 2018 and 2019, a drive starting from a team’s own 25 had an expected points value of 1.47 (the highest in history). So that’s saying that with largely unlimited time (that includes some time-limited situations, but more where time isn’t a factor) and with the possibility of a touchdown bumping that up, less than half of drives didn’t even produce a field goal. And in this game in particular, the Rams had 14 drives before this last one, producing three touchdowns and two successful field goals, so only 35.7 percent of their drives produced points even without clock limitations.

The data found here isn’t quite specific enough to say that either going down inside the one in the hopes of scoring later or scoring when the Bucs did is a better choice. What it does illustrate is that the Bucs’ chances were pretty good either way; a field-goal drive with 42 seconds left was relatively improbable, but so is being stopped on at least two plays from inside the one.

And what may be interesting to see here is if this leads to more discussion of scoring in the final seconds to tie; there’s been plenty of talk about the value of going down rather than scoring when that guarantees a win, and even sometimes when that lets you kill clock for a final-seconds field goal, but this specific situation of “score to tie the game or wait in the hopes of tying the game later” hasn’t received as much attention. We’ll see if that changes.

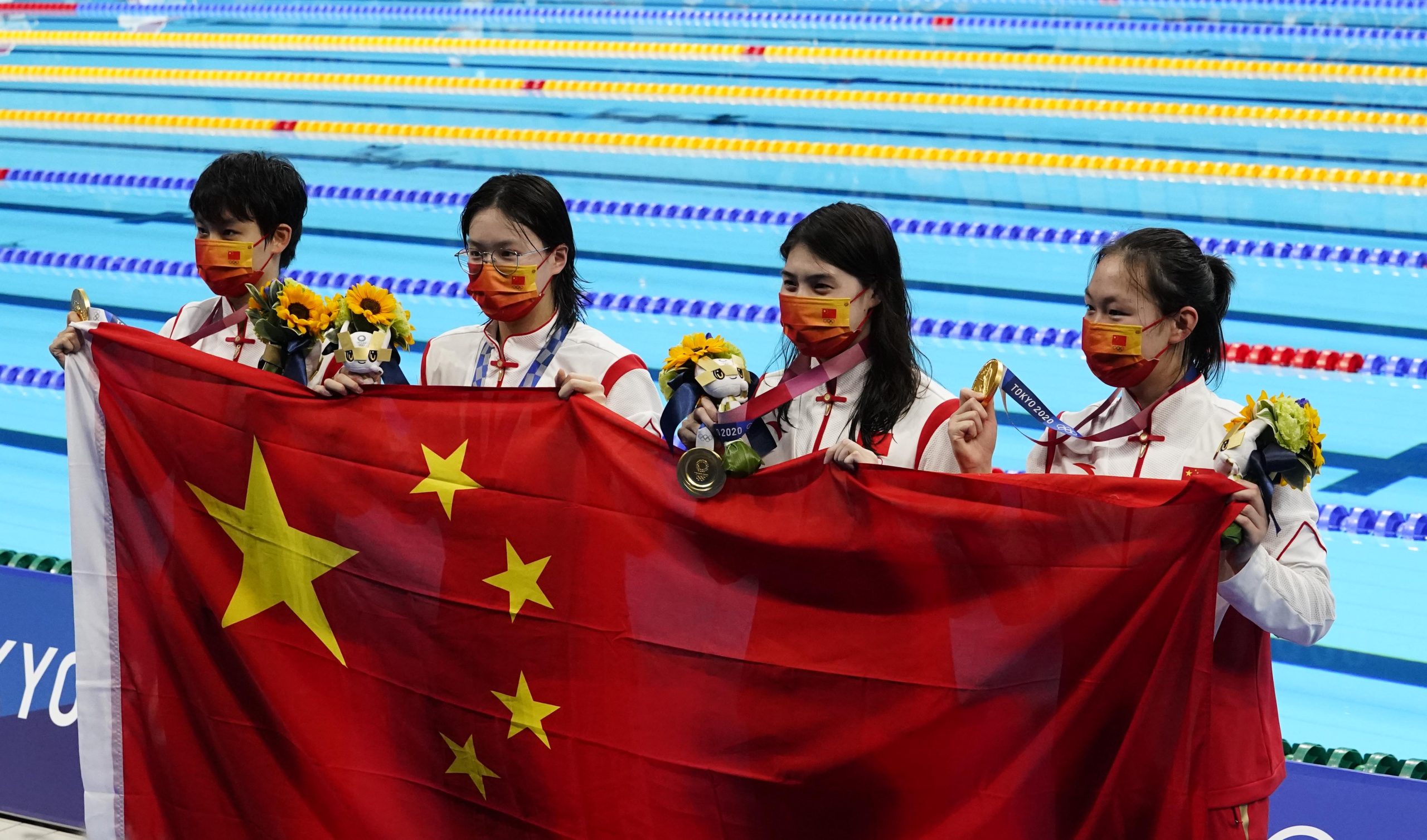

[Stathead, NFLFastR; photo from Matt Pendleton/USA Today Sports]