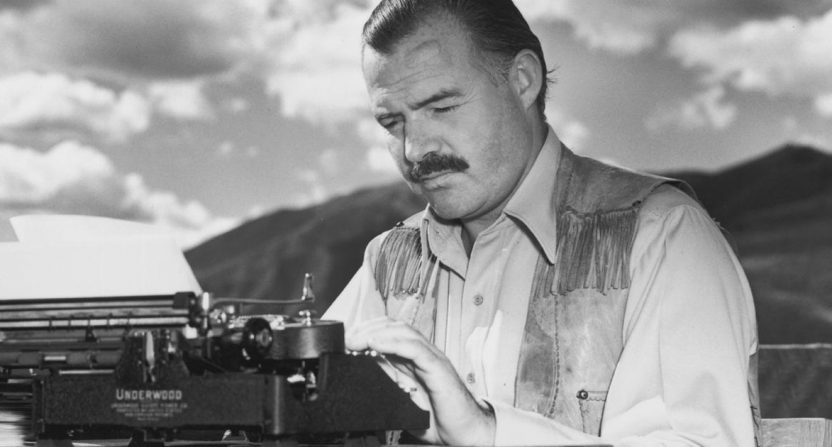

Author Ernest Hemingway was a legendary sportsman, with a passion for boxing, sailing, fishing, bullfighting, and hunting, among other pursuits. He also spent time on the front lines of both World Wars, survived plane crashes, and just about any other number of violent pursuits you can imagine.

And, of course, he killed himself.

The long-held belief was that Hemingway suffered from depression and alcoholism, which led to his suicide. But a new book from a very qualified source postulates that in fact, Hemingway suffered from CTE, a result of at least nine concussions sustained throughout his life. The Province has a full breakdown of the book, but here’s the main case:

In his new book Hemingway’s Brain, Andrew Farah, chief of psychiatry at High Point Regional Health System at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, refutes earlier theories that Hemingway was suffering from bipolar disorder, manic depression or even an excess accumulation of iron known as hemochromatosis.

By reviewing medical records, memoirs, biographies and even Hemingway’s changing writing style, Farah focused on nine major head traumas, the first of which was sustained in Italy during the First World War, when a shell landed three feet from Hemingway, knocking him out, killing a soldier right beside him and blowing the legs off another.

This would go a long way toward explaining why Hemingway’s treatment at the time seemed to have no effect:

Contrary to the common story that modern psychiatry failed America’s greatest living writer in his moment of need, Farah concludes that Hemingway in fact received the best care known to medical science at the time. But it was for the wrong illness, based on a false diagnosis.

Shortly before he shot himself Hemingway had received two courses of electroconvulsive therapy, which should have had a 90 per cent chance of improving his presumed illness of depression and related psychosis. But Hemingway got worse, and quickly, because while electroshock improves depression, for those suffering organic brain disease it acts as a stressor on a vulnerable nervous system, accelerating the patient’s decline.

This is a low-stakes theory, of course, as there’s no way to prove it one way or the other, and Hemingway has been dead for more than fifty years. But when you take everything into account, it does kind of make sense, right? It’s also yet another example of just how scary this disease can be, and why it’s important to monitor the effects it has on our athletes.