The concepts of offense and defense are prevalent in American sports. In basketball, it’s as though two separate games are going on simultaneously, with players judged differently based on their skillsets on either end of the court. Baseball is similar, but even less connected. Football just uses two completely different units.

Hockey’s extreme speed and constant threat of counter-attacks make for games that flow more than its traditional American counterparts, and thus attack and defense become slightly more intertwined. Players’ responsibilities change dramatically between each, even if offensive set-ups are faster and much less obvious to the casual observer’s eye.

Soccer, as a whole, conforms more toward hockey’s perception of offense and defense than basketball or football’s. Defenders are clearly labeled as such, and stay in a fairly plain line of three, four or five, but quick changes of possession and, especially in the modern game, increased pressing techniques diminish obvious differences between stages of the game.

Due to this increased flow, a soccer teams shape and formation does not change to as large an extent as other sports, beyond general basics and individual quirks. For example, many four-in-the-back teams spread their center backs apart from each other and push their full backs higher when in possession, allowing one midfielder to drop deeper and others to step higher into various open half-spaces. Some players take personal liberties, like Portland winger Darlington Nagbe, who operates closer to the “B-gaps” (the channels between CBs and FBs) in an effort to be more involved in possessional build-up and allow space on the flanks for overlapping left or right backs.

For the most part, though, managers do not seem to focus as much on developing attacking and defending shapes, for reasons with as much to do with personal clarity as they do with simplicity. Chicago Fire manager Veljko Paunovic, already having to be a creative tactician with the makeup of his roster, is the exception to this.

Paunovic has designed a system in Chicago that attempts to both take advantage of aging German elite Bastian Schweinsteiger’s game-breaking passing and hide his deficiencies, which revolve around his decreasing mobility and now increased tendency to give the ball away. With a talented, well-built roster at every position and one of MLS’ best defensive midfielders in Dax McCarty, Paunovic’s system is fits his complex team well, even if the tactics are equally intricate.

That system combines on-ball style with unique shifts in formation and team shape that often coincide with the loss or gaining of possession. It puts an emphasis on building from the back, using Schweinsteiger as the leader and fulcrum of it. The result is pretty soccer spearheaded by one of the best passers of this generation.

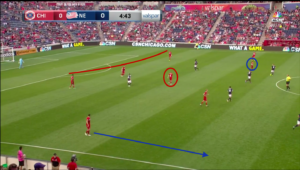

Their success and efficiency in possession could not be had without the tactical shape Paunovic has designed to create gaps in the opposition and make sure their spacing is exactly correct. Here is a screenshot of that shape from their recent domination of the New England Revolution:

As noted by red line, Schweinsteiger drops deep between the center backs to create a three-at-the-back — not a new concept, but a calculated one. Schweinsteiger is able to dictate the Fire’s possession patterns from this position (his hand signals and communication become obvious), while McCarty (circled in red) can step higher and 1) contribute to patient and intricate passing build-ups and 2) act as the first defender if the ball turns over.

Juninho (circled in blue), who became the odd one out in central midfield when Schweinsteiger arrived, started against New England and stepped higher in possession, filling central gaps and allowing versatile attacker Michael de Leeuw to play something closer to his preferred roaming second forward role from the wing. With the Dutchman often cutting inside, right back Matt Polster (who scored against the Revs) can overlap a ton, as noted by the blue arrow. Polster, a converted central midfielder, uses his patient possession instincts to contribute to the build-up, especially in the attacking half.

Chicago’s collection of some of the league’s best passers allows them to pass it around in the back and eventually hit line-breaking balls into gaps without getting smothered by pressing teams, like fellow MLS possession-hounds Columbus (or NYCFC, albeit only against Toronto). Paunovic moves his players around like chess pieces in this shape, creating space to move and opportunities for channel-running attackers like David Accam and Nemanja Nikolic to latch on to more adventurous balls.

Schweinsteiger and McCarty, at the same time, are allowed to do what they do best, themselves pushing and pulling players and making their teammates better by giving them the ball in the correct half-spaces. It is an intricate system with a lot of moving parts, and one that could not reasonably be used by any other MLS team, as much as Crew SCwant to replicate it.

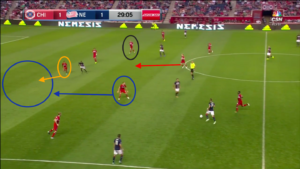

Defensively, they move into a completely different shape, one that changes slightly based on the situation and similarly utilizes a lot of different elements. Here is a screenshot from the Revs game that does not illustrate their general defensive shape, but rather shows their ability to adjust and cover different gaps relative to changing situations:

Again, a back three can be noticed, with Schweinsteiger (circled in black) this time on the outside of it. McCarty (in red) is jogging back to his position in front of that backline after stepping out to press a deeper New England possession. Normally, Polster (in blue) would be covering his natural right back spot, but given the fact that Schweinsteiger and McCarty are on the other side of the field and that de Leeuw has tracked back to mark Kelyn Rowe (No. 11), it is his responsibility to step out to the ball, which is pushed forward by Antonio Delamea (No. 19) with Diego Fagundez not far away.

Kei Kamara saw that Polster had stepped and tried to run into the vacated space, but Johan Kappelhof (in orange) is ready to run with him, knowing Joao Meira had the cover from Schweinsteiger and McCarty to fill Kappelhof’s space.

Delamea and Fagundez had a miscommunication literally seconds later and McCarty intercepted, but that image encapsulates the Fire’s defensive philosophy: cover every space on the field by correctly utilizing the smartest players (Bastian and Dax) and rotating perfectly in an ever-moving system. Mobility and versatility are key for these players (how many full backs in this league are comfortable in the position Polster is in there?) in order to execute Paunovic’s ideas.

You’ll notice how much they adjust between attacking and defending, and when watching their games closely, specified individual instructions are clearly in place. It’s calculated, if a bit risky due to human error and the lack of mobility of Schweinsteiger, and it has pushed them three points off the Eastern Conference leaders with a game in hand.

Paunovic has put himself at the top of the Coach of the Year race, and the Fire have made themselves one of the most unique and interesting tactical teams in MLS.