In England, they like to point out that just because you were a great horse, it doesn’t mean you’ll make a great jockey. While this imaying is something of an oversimplification, it nevertheless underscores the leap in logic required to think that a great soccer player – a great anything player, really – will make a good manager.

Yet again and again, the assumption has been made that a player who transcended his peers on the field will do the same along the sidelines. And that just never seems to work out that way – with very few notable exceptions.

Look at the list of the most successful managers in recent years, in recent decades even, and you won’t find a great many names among them that you’re likely to even remember from their playing days. Pep Guardiola and Luis Enrique stand out. They had strong careers but weren’t exactly all-time greats. Giovanni Trappatoni, Vicente Del Bosque, Jupp Heynckes, Carlo Ancelotti, Fabio Capello and, more recently, Diego Simeone were likewise reputable players.

Sir Alex Ferguson was a solid pro, but not a very memorable one. Ditto Louis van Gaal. And Marcelo Lippi. And Guus Hiddink, Ottmar Hitzfeld and Jurgen Klopp.

Arrigo Sacchi, Jose Mourinho and Rafa Benitez only played on the fringes of the professional game.

Now conduct the same exercise in reverse. Take the top-50 of World Soccer magazine’s greatest players of the 20th century list and consider how many of those players went on to have significant managerial careers.

Franz Beckenbauer won the World Cup with West Germany and claimed league titles with Olympique Marseille and Bayern Munich, also taking the UEFA Cup with the latter. Kenny Dalglish won the old First Division three times with Liverpool and again with Blackburn Rovers, in addition to two FA Cups. Johan Cruyff won La Liga four times in a row with Barcelona in the early 1990s, setting up the club’s La Masia academy in the process. He implemented a player development mechanism and club philosophy that laid the groundwork for two decades of staggering success.

http://gty.im/467237988

And… that’s it. Plenty of names on that list did become managers but failed, or never escaped the clutches of mediocrity. Diego Maradona and Ruud Gullit were disasters. Marco van Basten did only slightly better. Zico, Dino Zoff, Lothar Matthaus and Giuseppe Meazza held plenty of jobs but didn’t particularly distinguish themselves in any of them. And Jurgen Klinsmann, well, let’s just say the jury is still out on him.

There simply isn’t a demonstrable correlation between successful playing careers and managerial ones.

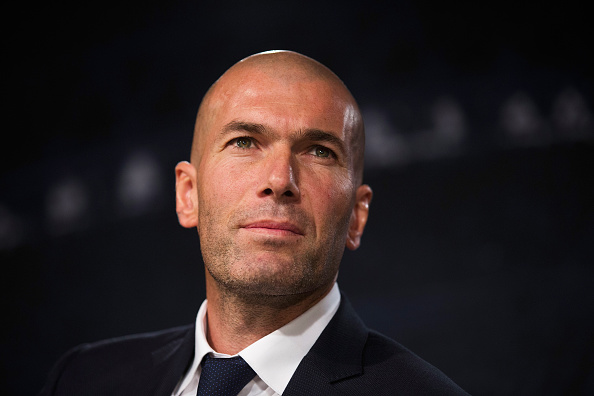

Which, of course, brings us to Zinedine Zidane, who was appointed as manager of Real Madrid on Monday. On the strength of a dazzling playing career as one of the best playmakers of all time, that is, because all he’s done as a coach is lead Real’s reserve team.

The best French player in history to lead the most prestigious club in the world – @lequipe pic.twitter.com/kqQoDnoJd0

— Real Madrid C.F. 🇬🇧🇺🇸 (@realmadriden) January 5, 2016

Zidane was ranked 28th on World Soccer’s list in 1999, although he would play for seven more years after it was released and would probably place higher today, if another all-time list were compiled. He is a bona fide great of the game, yet he takes perhaps the hardest job in soccer – with the expectations, the meddling and overbearing club president, the hopeless politics – lacking any kind of relevant experience. Although Real president Florentino Perez did point out that Zizou was an assistant when won the club finally won its tenth Champions League title in 2014 under Ancelotti, before he took over the B-team.

The belief, once again, is that he can sprinkle the same magic dust over his new charges that he did over the fields he bestrode a decade ago.

Real isn’t the only club making this sort of decision. Valencia appointed Gary Neville recently. And it can’t be ruled out that Manchester United won’t appoint Ryan Giggs sometime in the coming years – a player who, like Zidane, does qualify as a great, unlike Neville, Guardiola and Luis Enrique.

Because lately, this strange construct was lent some credence by Guardiola’s towering accomplishments with Barca upon receiving the same sort of baseless promotion from the reserve team. Luis Enrique won the treble for the club last year in his first in charge without much of a track record. His experience was limited to a year with Celta Vigo, another with AS Roma, and some time with Barca’s reserves.

They won’t be doing Zidane any favors. The precedent set is essentially one of inexperienced coaches at one of Spain’s two juggernauts winning the league, the cup and the European title in their first years. Measured against those quasi-aberrations, the Frenchman is being set up to fail.

http://gty.im/473062088

Because while Zidane isn’t stepping into a crisis, exactly – since Real is very much in the title hunt and alive and well in its continental campaign – he’ll now oversee a team still seething about the firing of Ancelotti last summer, which scapegoated his successor Benitez.

Zidane will have to massage Perez’s obsession with Gareth Bale’s success while reconciling it with his problematic compatibility with the rest of Real’s attack. Zidane is expected to jam a square peg down a round hole. And to juggle every other stakeholder’s in the complex mosaic of competing interests at the club.

Far more experienced managers have failed miserably in Madrid. Now Zidane will hazard all he really has, his good name. If he succeeds, he’ll prove the rare exception to a merciless rule.