“I quit.”

“I’ve had enough of this.”

“I’ve seen enough. I’m through with this.”

At some point in our adult lives, we’ve felt these thoughts. Maybe we haven’t acted on them, but we’ve felt them. We’ve also seen enough situations — maybe in our own experiences, maybe in the lives of others around us, maybe in the lives of public figures we see in sports or politics — to get a sense of why people quit.

The complicated — and complicating — aspect of quitting: The word (not so much the act) carries a hugely negative weight and connotation. To be more precise, if you quit, you are labeled “a quitter.” The word can define you and stick with you — maybe it doesn’t, but for many, the association is powerful. For some, the association is permanent.

That seems like a Scarlet Letter of sorts, a cross to bear throughout one’s life.

If it’s deserved, it’s not really an issue.

However, what if it’s not?

*

The issue of quitting in sports (not just any part of life, but the specific theater of athletic competition) has re-emerged in the wake of Steve Spurrier’s abrupt decision to step away from coaching the South Carolina Gamecocks, which likely marks the end of his head coaching career.

Spurrier did quit. It is a fact that he quit. We will discuss Spurrier’s situation in a separate stand-alone piece, but the purpose of this piece is not to render a verdict on the Head Ball Coach. It is to take a broader view of quitting — in sports beyond college football, and in the whole of life itself.

Is quitting ever acceptable?

To whom — or what — must a person be most loyal when s/he contemplates quitting?

It doesn’t seem important (or even necessary) for me, as a writer, to answer these questions or claim to have the right answers in the first place.

The main thing I’d like to see here is for Americans to ask themselves these and other questions about quitting, in order to re-examine their views of this term, freighted as it is with powerful and highly adhesive qualities.

*

Here, then, are various examples of quitting, in and beyond sports — including but not limited to football:

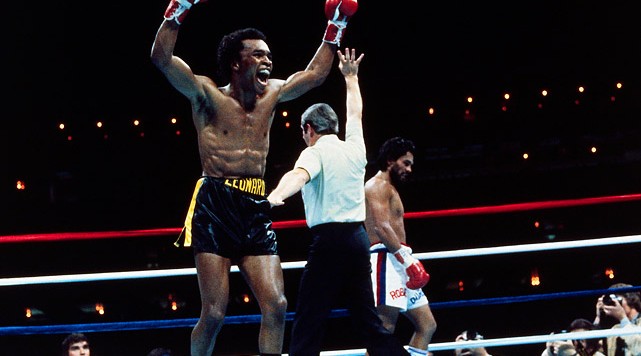

One of the more infamous examples of quitting was Roberto Duran’s “No Mas” moment against Sugar Ray Leonard in November of 1980:

That seems like a classic example of a coward’s way of quitting, truly the kind of thing any competitive person should loathe. Duran was intimidated and humiliated. He won the previous bout with Leonard only five months earlier, in June of 1980, so he had the added obligation of defending his victory and championship with honor, and he seemed to back out.

Yet, to underscore the lack of easy, linear simplicity on this larger matter of quitting, Duran might not have wanted to absorb more physical punishment in a sport which has killed many people through the years. In fact, not that long after “No Mas,” a boxer did in fact die because of a willingness to continue to stay in the ring and not quit.

Anyone remember Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini and Duk-koo Kim in November of 1982, just two years after Roberto Duran quit?

The New York Times produced a story on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the fight, in 2012.

The simple summary: Kim died shortly after the fight. His mother committed suicide a week before Mancini’s next fight a few months later. Under a year after the fight, the referee — Richard Green — died. It is still believed to this day that he committed suicide.

This is because a young Korean boxer refused to quit.

There is no verdict or judgment in that sentence, no implied statement on the merits of quitting. It is merely a fact. We are left to make of it what we will.

While we’re on the subject of quitting violent sports, then, what about Chris Borland of the San Francisco 49ers (formerly the Wisconsin Badgers) quitting football at an early age, without CTE or the accumulated effects of concussions? Is that form of quitting more — or less — acceptable than anything one might see in boxing? Is it — to raise another example — more or less acceptable than it is for a 34-year-old player to call it a career? (Borland retired at the age of 24.)

Let’s discuss coaches very briefly. Should it matter — and should it therefore affect our views — if a coach quits in the middle of an 82-game basketball season as opposed to a 12-game football season? Should it matter if a coach retires or — in Bobby Petrino’s case with the Atlanta Falcons and Arkansas Razorbacks — quits in order to leap to another job, crossing the pro-to-college divide?

Should it matter if a coach is 70 years old, in Spurrier’s case, or 50 years old, free from questions about age being able to affect his ability to recruit?

Quitting, as you can see, acquires many forms — in the back of our minds, we know this, but we might need to be reminded of the scope “quitting” can and does attain.

Speaking of the scope of quitting, what about realms beyond sports?

Was Al Gore a quitter, in the negative sense of the term, to concede the 2000 presidential election result when he did? Many would say no, but some would say yes.

To use a fictional example — but one which has in fact played out for millions of women — did Joan Holloway-Harris, near the end of Mad Men, quit at McCann-Erickson in the pejorative sense of the term, costing herself a lot of money and influence in response to sexual attitudes in the workplace which probably wouldn’t have been that different if she went elsewhere in 1970? Or, did she make a liberated decision, an assertion of her independence, with Jim Hobart bearing the responsibility for making Joan quit?

*

Quitting is a pervasive reality.

The real question is whether quitting — in various situations and scenarios — is something to abhor or applaud. Almost always, it’s the former in this culture.

Should it be, though? Should people be weighed down by the burden of society’s verdict, when the specifics of a situation might not warrant the negativity that’s so commonly associated with quitting?

I won’t answer those questions. You don’t even have to answer them right now.

You should, however, give them some thought and contemplation.