Sun Life Stadium and the city of Miami have hosted many big games over the years. The first College Football Playoff semifinal between the Oklahoma Sooners and the Clemson Tigers won’t become the most memorable clash ever staged in South Florida, but as kickoff time approaches, this game has already been defined in many ways.

The Best of 2015

- The 15 People Who Had the Best Year of Anyone on the Planet in 2015

- The 15 Most Memorable Moments of 2015

- The 15 Best Songs of 2015

- The 15 Biggest Sports Storylines of 2015

- The 15 Best Teams in Any Sport in 2015

- The 15 Best Female Athletes of 2015

- The 15 Best Male Athletes of 2015

- The 15 Best Games of 2015

- The 15 Best Coaching Jobs of 2015

- The 15 Best New TV Shows of 2015

- The 15 Best Superheroes of 2015

The Orange Bowl game always had a home at the Horseshoe in Little Havana. Nebraska and Oklahoma won national championships in the Orange Bowl stadium. Arkansas denied OU a national title there. Miami rose to prominence there in the 1984 game, arguably the greatest ever played.

Yet, for all the history which flowed through the Orange Bowl game over the years, the most important football contest ever played in the Orange Bowl stadium was a professional one. This reality begins to shape the context in which Oklahoma and Clemson take the field on Thursday in Sun Life Stadium.

Embed from Getty Images

When Joe Namath sat by a pool with Brent Musburger and other reporters in the days before Super Bowl III in 1969, he breathed the easy confidence of a man certain his New York Jets were going to beat the Baltimore Colts. Americans don’t remember Namath for his guarantee that the Jets would win; they remember him because he made good on the guarantee.

History is littered with athletes and coaches who talked tough in the days before a big game but couldn’t walk the talk. If history does remember losing athletes in a big game, it’s either for their ability to perform beyond all expectations in the face of daunting odds (think of Ron Vander Kelen of Wisconsin in the 1963 Rose Bowl against USC)… or for a humiliating failure. One example of a failure occurred in the Orange Bowl stadium, as Jackie Smith of the Dallas Cowboys dropped that easy touchdown pass in Super Bowl XIII in 1979.

WTF?

- How Is This a Thing: A Hot Dog Wearing Pants Take

- Man dies in Germany after condom machine blows up

- Pau Gasol’s take on Chicago-style pizza is not wrong

- Times Square Olive Garden charging $400 per head on New Years Eve

- Laveranues Coles sues for the right to open a bikini bar

- Rams defensive end William Hayes says he doesn’t believe in dinosaurs

Eugene Robinson had long been regarded as one of the NFL’s best citizen-athletes, active in community service and outreach. Yet, the night before his Atlanta Falcons played their first Super Bowl — XXXIII against the Denver Broncos — Robinson was arrested for soliciting a prostitute.

On gameday, Robinson took the field, but his mind and body were not there. Rod Smith and other Denver receivers torched Robinson. It should have been the night for Robinson to be at his best. Yet, his bad-boy moment led to a body-snatched performance, his lowest point as a professional.

With Super Bowl III in 1969 or Super Bowl XXXIII in 1999, huge football games are sometimes remembered for the peripherals rather than the substance of the games themselves. In college football, the city of Miami rooted for a team whose championship-game experience is also remembered for something which happened off the field.

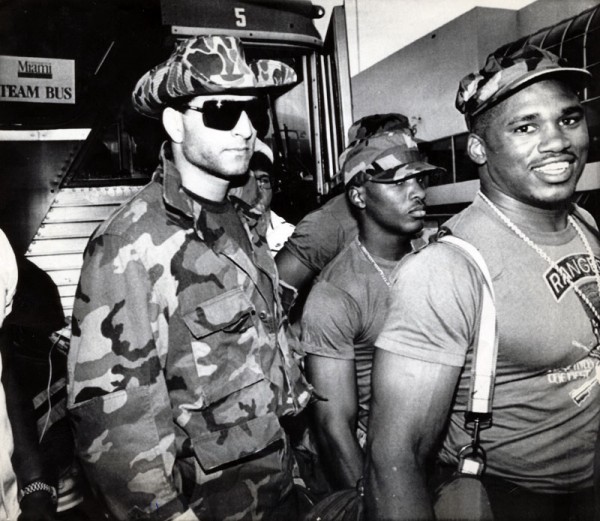

Remember this, from the banquet just before the 1987 Fiesta Bowl showdown between No. 1 Miami and No. 2 Penn State?

Miami could have allowed the quality of its play to do the talking, but the Hurricanes felt the need to go out of their way and display their arrogance before winning a championship. If Joe Namath’s confidence was solid and real, Miami’s external appearance manifested inadequate mental and tactical preparation, at least on the offensive side of the ball. Vinny Testaverde just got intercepted again by Penn State, in fact.

As we pivot to Oklahoma-Clemson, it is already apparent that the 2015 Orange Bowl — this College Football Playoff semifinal — will be remembered as a game in which the loser set itself up for a fall with its game-week actions.

Embed from Getty Images

Some will say that an X-and-O preview is the best way to size up a game. In many cases, that’s true. However, when a flurry of incidents colors the 72 hours before kickoff time, psychology becomes the central tension point.

One has to wonder about the clarity of mind possessed by Oklahoma’s Joe Mixon after he had to confront the press and shut down non-football questions at media day on Tuesday, offering less than fully expansive (or charitable) answers about his past. (Were these answers necessary from a legal standpoint? Perhaps. Yet, the mere experience of media day could cloud Mixon’s mind. Oklahoma can’t be completely at ease about his gameday readiness.)

The Good Stuff

No, Mayfield didn’t say anything one would call “mean.” Confrontational, yes, but nothing outrageous. Yet, Mayfield got a lot off his chest. Therapy, or a cluttered mind focused far too much on things other than dissecting Clemson’s defense? We’ll find out on Thursday, but if Mayfield struggles, we all know how his failure will be framed… and moreover, it will be hard to escape the notion that he craved respect more than he wanted to work to attain it.

All the controversies and distractions preceding the Orange Bowl had revolved around Oklahoma as of Tuesday afternoon, but as the day turned into evening, the story broke that three Clemson players — including No. 2 receiver Deon Cain — were sent home for failing drug tests. The Tigers have lost an important cog in their offense; moreover, this loss occurs with relatively minimal time to readjust.

One of the foremost talking points surrounding this game — just after the matchup became official on Dec. 6 — was that Oklahoma had faced backup quarterbacks in each of its last three games, against Baylor, TCU, and Oklahoma State. The Sooners won’t face a backup quarterback at the start of this game, but they will now play against a number of backup receivers.

Embed from Getty Images

It’s not as though the performance, the technique, and the tactics won’t matter on Thursday, in the first daytime Orange Bowl game since Auburn and Nebraska met in 1964. Yet, Oklahoma and Clemson have to be present — awake, focused, clearheaded — in order to implement the game plan and perform the actions needed to produce a victory.

More than enough events have occurred — not too long before kickoff — to suggest that the biggest challenge for both the Sooners and the Tigers is the one between the ears.

It’s not about heart — these teams have passion oozing out of their insides.

It’s not about feeling disrespected — that storyline has already been worn out.

It’s not about OU avenging the 2014 Russell Athletic Bowl or Clemson wanting to show that its blowout of the Sooners a year ago was no fluke.

The Orange Bowl has become a test of sweeping away the clutter and the gray clouds of emotions. This first semifinal will be decided by the team which gets out of its own way.

The team which succeeds will march on to the national title game in a week and a half. The loser will be remembered not for what happened in this contest, but for the events which preceded it on Monday and Tuesday.

Embed from Getty Images

While Michigan State and Alabama have enjoyed a comparatively quiet buildup to their semifinal, Oklahoma-Clemson has tackled a ton of turmoil and tumult before the shouting starts.

A bad-boy semifinal beckons, on an afternoon when the emotional volatility at work in this matchup points to the very real possibility that an early 14-point deficit — either way — could lead to a wipeout loss. An avalanche of first-quarter adversity could produce a “no mas” moment, something akin to what both teams have experienced inside Sun Life Stadium in an Orange Bowl game.

Oklahoma quit after Mark Bradley muffed a punt in the 2005 Orange Bowl (that season’s national championship game) against USC. Clemson surrendered 70 points to West Virginia in the 2012 Orange Bowl.

Given the distractions enfolding both teams, don’t be too surprised if a disastrous start for one team marks the beginning of a tsunami in this coastal city. Should such a scenario occur, Eugene Robinson and the 1986 Miami Hurricanes will be able to relate to the team which absorbs a beatdown.

Yes, if Oklahoma and Clemson can both play heaven-kissed football and stage a classic, no one will remember the fluff and noise of the past 72 hours. Let’s hope for that outcome on New Year’s Eve… but don’t bet on it. Sooners-Tigers has acquired a chaotic contour, conspicuously close to kickoff. Given that these are 19- and 20-year-old men thrust into a spotlight whose intensity they have never known before, history tells us to expect raggedness and volatility instead of smooth and clinical excellence.

Getting out of their own way — that’s the mountain the Sooners and Tigers must climb in Miami.